Blog

The Constitutionality of Geofence Warrants

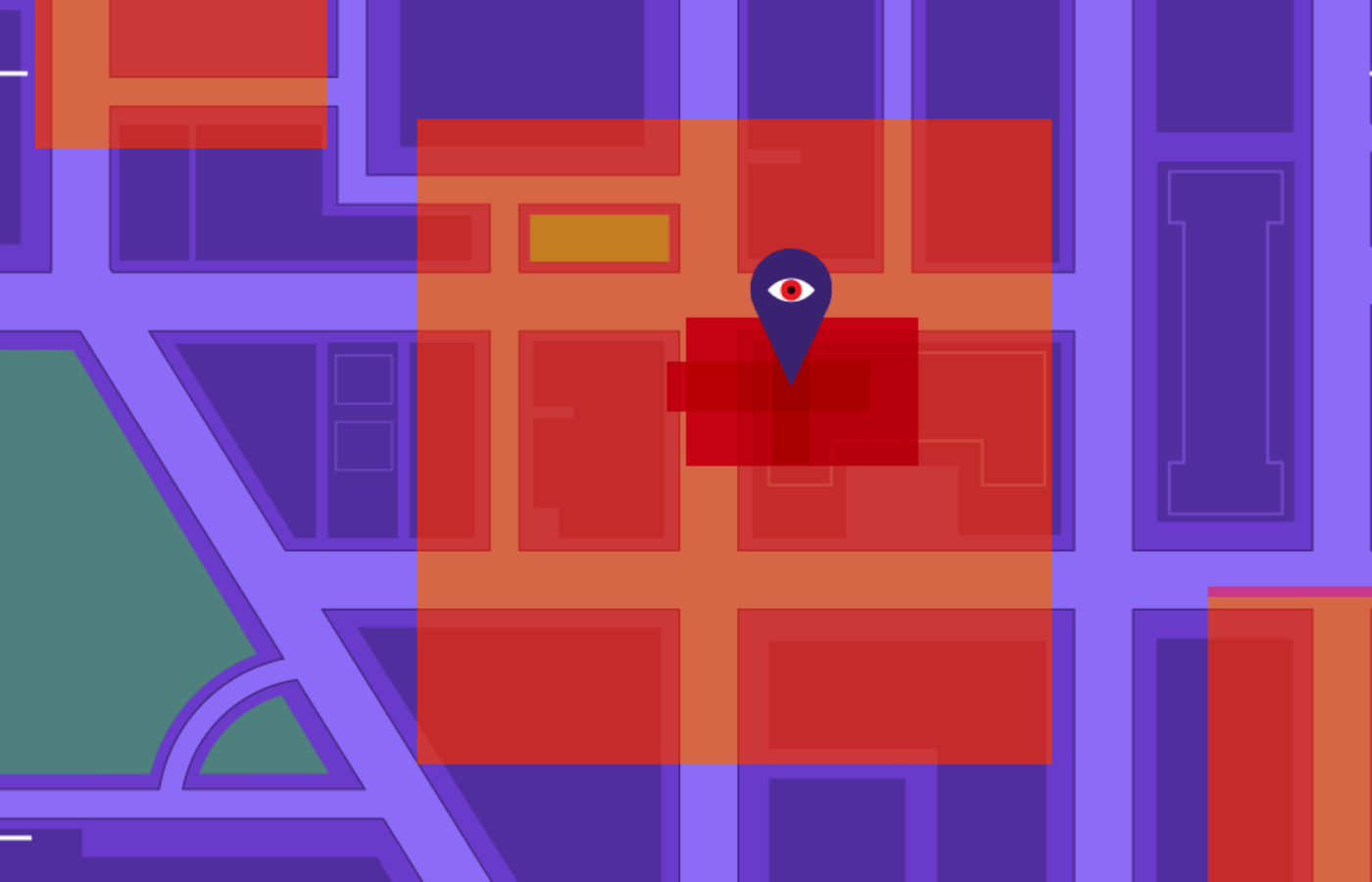

Image via The Electronic Frontier Foundation

Geofence warrants allow law enforcement to use databases in order to determine who was in a particular area at a certain time. These search warrants are used to compel private companies to hand over geolocation data on all users and devices in a specific “geofence” area. These warrants are atypical because they don’t name a particular suspect or group, instead they are used to obtain information indiscriminately.1

Google’s database–called Sensorvault–contains detailed location records on hundreds of millions of devices around the world. This database is connected to Google’s Location History, which collects data when people use apps such as Google Maps.2 This data is stored indefinitely and goes back nearly a decade.3 For years, the police have used warrants to obtain location data on specific people. But geofence requests allow law enforcement to receive a whole swath of data in an area without targeting a specific suspect.4

In a typical case, Google provides the police with an anonymous ID number for each device found within a geofenced area, plus information about exactly when and where within the “fence” each device was seen. Next, the police identify a subset of those devices to ask for additional information on where the devices traveled over a period of time. The police may also ask Google to “unmask” certain anonymous users and provide more detailed information about them, including their names and phone numbers.5 In 2020, Google received 11,554 geofence warrants from law enforcement.6

These warrants were used on an unprecedented scale in order to identify over 5,000 devices at the US Capitol during the January 6th riot. The FBI were able to identify phones that were on airplane mode or out of service, and even received data about users who had attempted to delete their location history after the fact. In fact, the attempts to delete location history after the riot were used by the FBI to single out 37 individuals for further investigation.7

Geofence warrants were also used to identify people at George Floyd protests in Minneapolis8 and protests in Kenosha, Wisconsin following the killing of Jacob Blake.9

What is protected by the Fourth Amendment?

The Fourth Amendment protects “persons, houses, papers, and effects” from “unreasonable searches and seizures” by the government.10 A government “search” is presumptively illegal without a warrant. In Katz v. United States, the Supreme Court held that a “search” implicating Fourth Amendment rights occurs whenever the government violates a person’s “reasonable expectation of privacy.”11

In 2018, the Supreme Court addressed the related issue of access to cell-site location information (CSLI) in Carpenter v. United States.12 CSLI refers to information collected by nearby cell towers which can be used to track the location of a cell phone. The third-party doctrine, established by United States v. Miller (1976) and Smith v. Maryland (1979), states that there is no expectation of privacy for information that is voluntarily shared with others.13 But, in Carpenter, the Court held that the compelled disclosure of CSLI was a Fourth Amendment search.14 The Court determined that, although the data is owned by wireless carriers – and thus was given “voluntarily” to a third-party – in the modern day, a phone is a necessity and you can’t “opt-out” of automatically created cell phone records.15 Thus, there is a “reasonable expectation of privacy” regarding CSLI.16

Is there a “reasonable expectation of privacy” regarding geolocation data?

Few courts have addressed geolocation directly, and those few have avoided deciding that question. In the 2022 case United States v. Chatrie, a Virginia district court held that it did not need to decide “whether Chatrie has a reasonable expectation of privacy in the data sought by the [geofence] warrant.”17

Some have argued that people can “opt-out” of Google location services and therefore, consumers are voluntarily giving up their geolocation to a third party.18 However, the ability to opt-out is murky. Location history is off by default, but users are prompted to opt-in “multiple times across multiple apps,” including when first using Google Maps, Google Photos, and Google Assistant.19 After that, Google is “always collecting” and storing that data across every app and device associated with a person’s account, even after a user deletes the app because Location History is tied to the account, not an app.20 Plus, even if it was easier to opt-out, location history is still a ubiquitous part of life, similar to how the Supreme Court determined that phones are a modern necessity in Carpenter. Thus, even if users have knowingly or unknowingly opted-in, there is still a reasonable expectation of privacy regarding geolocation data, especially since geolocation data can reveal a person’s location and movement at a much more precise level than CSLI.21

Do geofence warrants violate the Fourth Amendment?

Courts have only recently begun to address geofence warrants. In April 2023, the California Court of Appeal was one of the first courts to review a geofence warrant in People v. Meza.22 The Fourth Amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and guarantees that no warrants are issued unless there is probable cause and “particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”23 In Meza, the court held that the geofence warrant in the case was unconstitutional because it “lacked sufficient particularity” and “was overbroad.”24 The warrant did not meet the particularity requirement because it gave law enforcement “unbridled discretion” in requesting additional information “without restriction on how many users could be identified.”25 And it was overbroad because it “authorized the identification of any individual within six large areas without any particularized probable cause as to each person or their location” and the search boundaries were not as narrowly tailored “as they could have given the information available."26

Likewise, in the aforementioned United States v. Chatrie, the federal court held that a geofence warrant was unconstitutional because it failed “to establish particularized probable cause to search every Google user within the geofence.”27 To authorize the search of everyone in an area, the warrant must show probable cause that “all persons on the premises at the time of the search are involved in the criminal activity.”28 The court stated that “it is difficult to overstate the breadth of this warrant, particularly in light of the narrowness of the Government’s probable cause showing.”29 The only thing the police knew was that the perpetrator “had a cell phone in his right hand and appeared to be speaking with someone on the device.”30 After the police failed to locate the suspect after reviewing camera footage, talking with witnesses, and pursuing two leads, the “Government then requested location information for every device within that area.”31

In both Meza and Chatrie, the courts determined that the particular geofence warrants in the case were unconstitutional. The Chatrie court repeatedly emphasized that “this particular Geofence Warrant is invalid” (emphasis added).32 But no court has yet determined that geofence warrants in general are unconstitutional. In fact, even though both Meza and Chatrie found that the warrants were unconstitutional, the courts refused to suppress the evidence obtained from the warrants on the grounds that the officers relied in good faith on what they thought were legally valid warrants.33

Thus, in Chatrie, the court identified the major issue at the core of these warrants, finding “that current Fourth Amendment doctrine may be materially lagging behind technological innovations.”34 Police often withhold the invasiveness and capabilities of novel surveillance tools from judges, in order to get around issues of unconstitutional searches and they are able to use “good-faith exceptions” when the use of these tools are eventually challenged.35 Although the constitutionality of geofence warrants will eventually be decided by the courts, the larger problem is that by the time our legal system catches up, law enforcement are often onto the next cutting-edge surveillance tool.

What is the solution?

The Chatrie court urged a legislative solution to the problem of geofence warrants, stating, “thoughtful legislation could not only protect the privacy of citizens, but also could relieve companies of the burden to police law enforcement requests for the data they lawfully have.”36

Bills in New York, Utah, Missouri, and California are being proposed to ban or limit geofence warrants. And although so far the one in New York has failed to pass and the one in California is stalling, there is hope given the bipartisan support this issue has garnered.37

But even this focused legislative action may not be enough, because much of the data available via geofence warrants can also be purchased by law enforcement on the private market. Companies like Fog Data Science buy billions of cell phone-location data points and then state and local police are able to buy access to its database for less than $10,000 a year.38

In conclusion, our legislature must be more proactive in protecting our data from the abuse of law enforcement. Passed in 2015, CalECPA, which protects the privacy of California residents by requiring law enforcement agencies to obtain a warrant in order to access location information, was a good start.39 But, Congress must go further. There is a billion dollar industry in selling surveillance tools and data to private companies and the government. Courts will likely decide that geofence warrants are unconstitutional, but Americans need comprehensive federal laws for this decision to be truly effective.

1 Jennifer Lynch, First Appellate Court Finds Geofence Warrant Unconstitutional, EFF (Apr. 24, 2023).

2 Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Google’s Sensorvault Is a Boon for Law Enforcement. This Is How It Works., NY Times, (Apr. 13, 2019).

3 Jennifer Lynch, Google’s Sensorvault Can Tell Police Where You’ve Been, EFF (Apr. 18, 2019).

4 Google’s Sensorvault Is a Boon for Law Enforcement. This Is How It Works.

5 Mark Harris, How a Secret Google Geofence Warrant Helped Catch the Capitol Riot Mob, WIRED (Sep. 30, 2021).

6 Queenie Wong, Police Like Using Google Data to Solve Crimes. Does That Put Your Privacy at Risk?, LA Times (Jul. 24, 2023).

7 Mark Harris, A Peek Inside the FBI’s Unprecedented January 6 Geofence Dragnet, WIRED (Nov. 28, 2022).

8 Zack Whittaker, Minneapolis Police Tapped Google to Identify George Floyd Protestors, TechCrunch (Feb. 6, 2021).

9 Russell Brandom, How Police Laid Down a Geofence Dragnet for Kenosha Protestors, The Verge (Aug. 30, 2021).

10 U.S. Const. amend. IV.

11 Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347, 360 (1967).

12 Carpenter v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 2206 (2018).

13 138 S. Ct. at 2216.

14 138 S. Ct. at 2223.

15 Orin Kerr, The Fourth Amendment and Geofence Warrants: A Critical Look at United States v. Chatrie, Lawfare (Mar. 12, 2022).

16 138 S. Ct. at 2219.

17 United States v. Chatrie, 590 F. Supp. 3d 901, 935 (E.D. Va. 2022).

18 The Fourth Amendment and Geofence Warrants: A Critical Look at United States v. Chatrie.

19 590 F. Supp. 3d at 909.

20 Id.

21 NACDL Fourth Amendment Center, Geofence Warrant Primer.

22 First Appellate Court Finds Geofence Warrant Unconstitutional.

23 People v. Meza, 90 Cal.App.5th 520, 534 (Cal. Ct. App. 2023).

24 Id. at 537, 539.

25 Id. at 538.

26 Id. at 539.

27 590 F. Supp. 3d at 929.

28 Id. at 928.

29 Id. at 930.

30 Id.

31 Id.

32 Id. at 927.

33 590 F. Supp. 3d at 925; 90 Cal.App.5th at 543.

34 590 F. Supp. 3d at 925.

35 ACLU Argues Evidence From Privacy-Invasive Geofence Warrants Should be Suppressed, ACLU (Jan. 30 2023).

36 590 F. Supp. 3d at 926-27.

37 Albert Fox Cahn and Nina Loshkajian, The Police Surveillance Tool Too Dangerous to Ignore, Slate (Jun. 5, 2023).

38 Bennett Cyphers, Inside Fog Data Science, the Secretive Company Selling Mass Surveillance to Local Police, EFF (Aug. 31, 2022).

39 Explanation of the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act (CalECPA), Law Offices of John D. Rogers (Jan. 21, 2023).