Blog

Public Defense and Padilla: Structures and issues at state-level offices

Photo by Katrin Bolovtsova via pexels

Fifteen years ago, in Padilla v. Kentucky, the Supreme Court decided that constitutionally adequate representation of noncitizens in criminal cases requires advice on the immigration consequences of plea deals.[1] The Court reasoned that although immigration consequences are “collateral” to criminal charges, they are so important to defendants and so closely tied to the criminal process as to implicate the Sixth Amendment’s protection.[2] Commenters at the time described Padilla as the “most important right to counsel case since Gideon,”[3] a “revolutionary shift in perspective and daily practice.”[4] Today, however, some suspect that the shift has been less than revolutionary. In the words of immigration scholar Cesár Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, “[defense lawyers] know they’re supposed to say something, but they’re often saying as little as possible. Mostly because it’s a lot of work.”[5]

Recently, academic research has begun to examine the impact of Padilla in practice. In their seminal article Restructuring Public Defense After Padilla, Ingrid Eagly and her colleagues examined how public defenders in every county of California managed representation of noncitizens in criminal trials.[6] Eagly chose California for its high immigrant population and delegation of public defense policy decisions to its counties, making each county a “laboratory for local experimentation with the representation of immigrants charged with crimes.”[7]

This paper expands on Eagly’s research by documenting public defenders’ approaches to Padilla in states that organize public defense at the state level. While the federal constitution requires states to provide attorneys to indigents facing criminal charges,[8] states are free to structure the provision of indigent defense as they wish.[9] In total, twenty states organize public defense at the state level for all crimes likely to carry immigration consequences.[10] In addition to using a different public defense mechanism, these states also differ from California in their substantive criminal law and protections of noncitizens.[11] While some of these states have relatively small immigrant populations, their public defenders still must meet Padilla’s mandate for each noncitizen client.

This paper makes four significant findings. First, the structures used in states surveyed are similar to what Eagly noted in California counties, with widespread use of expert consultants, screening questions, and, in some cases, policy advocacy.[12] Second, new data on advisal numbers in five states suggest that some states are likely failing to identify noncitizen clients,[13] an issue that better screening procedures could fix. Third, in several states surveyed, the caseloads of immigration experts are higher than Eagly recommended.[14] Fourth, there is an unmet need for better training and networking for public defenders managing their state’s representation of noncitizens, particularly given increased enforcement in the second Trump administration.

1. Methodology

This paper is based on information gathered through a combination of email, phone, and virtual video interviews with individuals involved in the provision of public defense in each state. I asked the experts loosely structured questions, borrowing subject matter from Eagly and her colleagues.[15] I also asked respondents to send me copies of any documents they were willing to share, and supplemented the interviews with independent research.

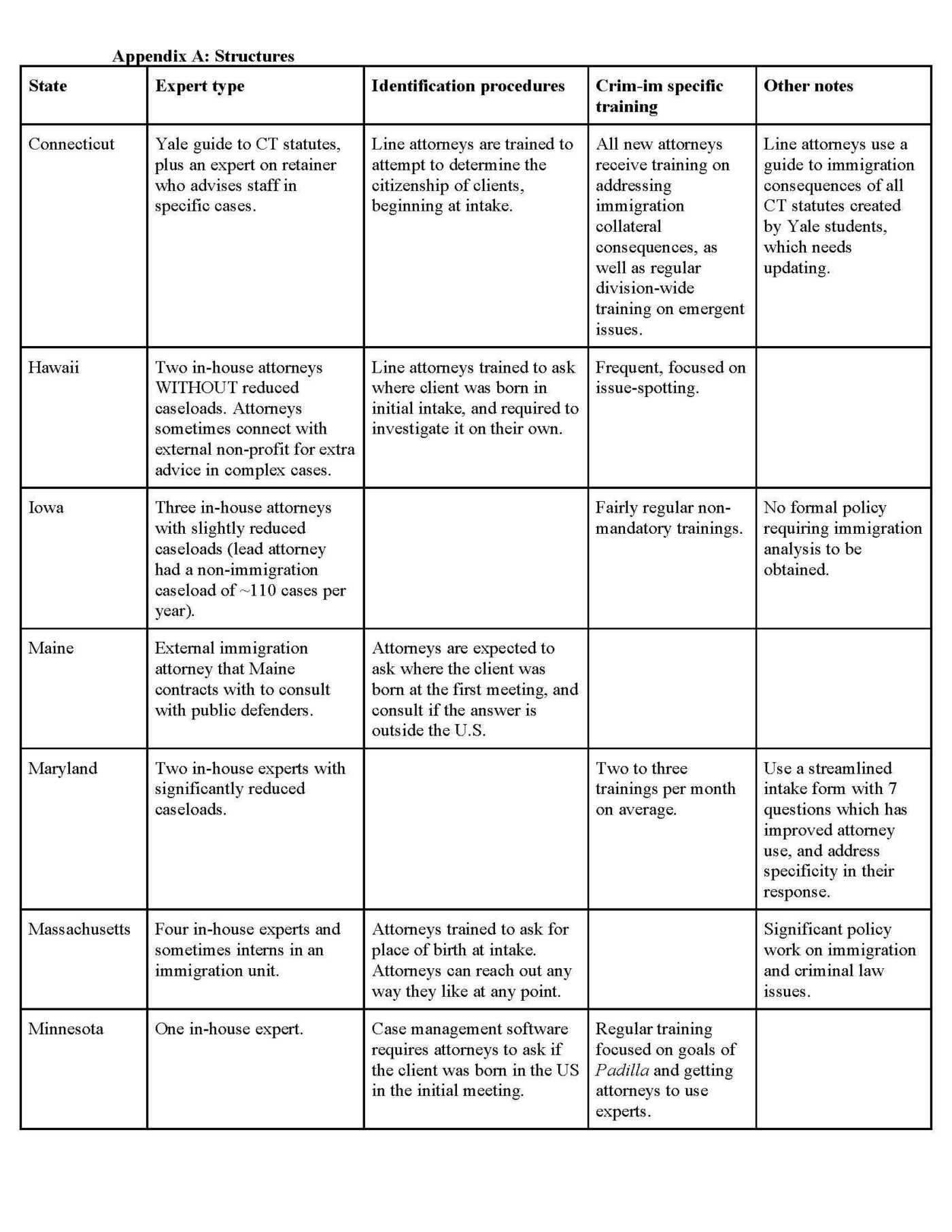

In total, I was able to contact and interview experts in 17 out of 20 states with state-level public defense services. Appendix A and Part 2, below, summarize my findings. I spoke with state chief public defenders, training and professional development experts, in-house immigration experts, and line attorneys. The majority of respondents were passionate about representation of noncitizens in criminal matters, and knowledgeable about their state’s systems. However, a few people I spoke with had limited knowledge on this issue, and my calls and emails were ignored in the three states I was unable to reach.[16] The information in this paper is limited by the knowledge of respondents, and their willingness to answer my questions.

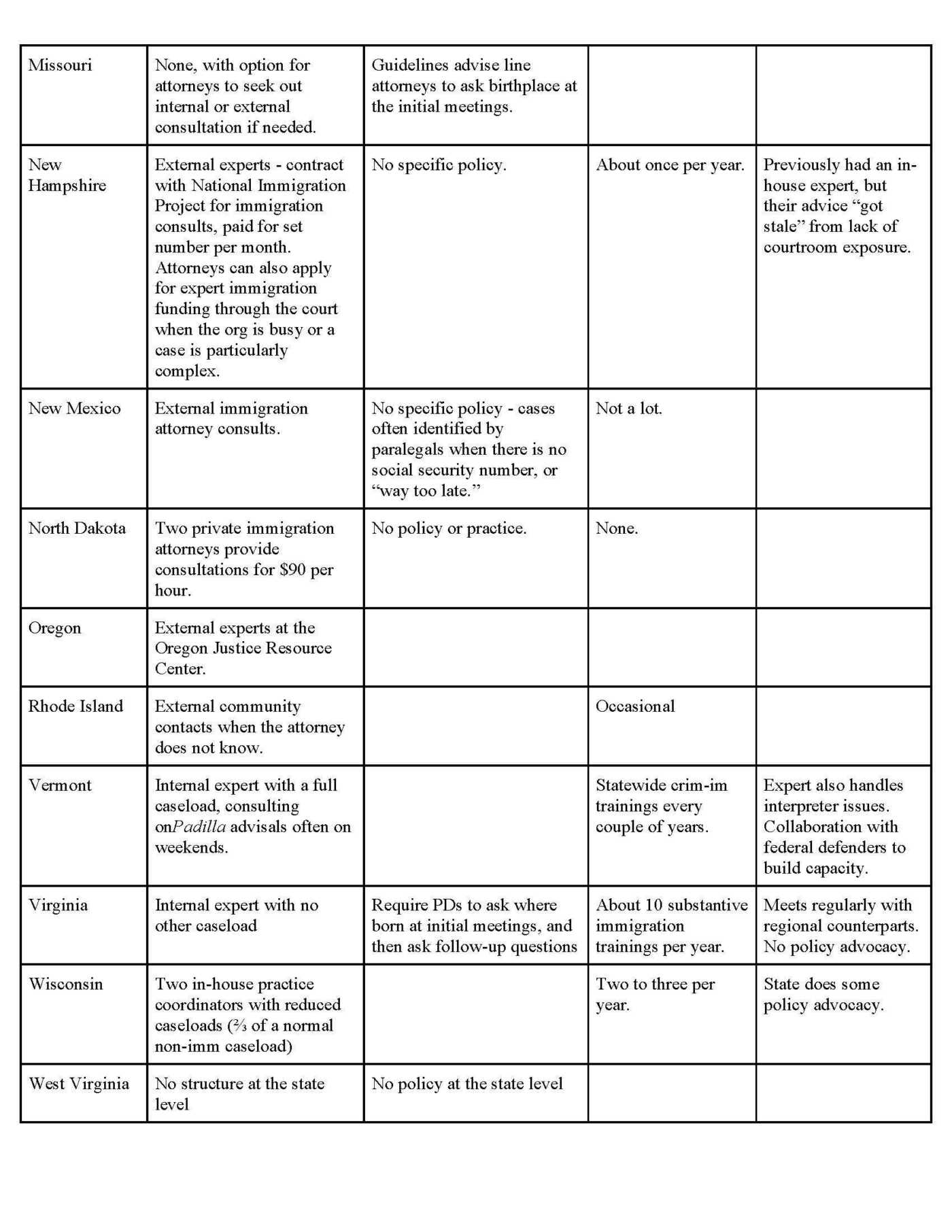

In Part 3 of this paper I assess issues in Padilla structures, in part by comparing state resources proportional to client populations. To do so, I use census data on the foreign-born population of each state, determined by multiplying the census percent foreign-born by the total state population.[17] This number is flawed for assessing the population that might need Padilla advisals for several reasons: not all foreign-born people are noncitizens,[18] census data may not accurately count undocumented people,[19] and prosecution rates may be more closely related to the racial make-up of a state’s noncitizen population than to the number of foreign-born individuals in that state.[20] Still, for purposes of this paper, the foreign-born population provides an adequate baseline for comparing states to each other at a high level.

Some individuals I spoke with for this paper feared retribution from the federal government if they spoke publicly about certain immigration issues, and asked me to only quote them anonymously. To that end, I have declined to cite specific sources for some statements that could put attorneys at risk.

2. Structuring Criminal Representation of Noncitizens

To meet Padilla’s mandate, public defenders must identify noncitizens, determine the immigration consequences of potential plea deals, and communicate that information to clients sufficiently to allow them to make an informed decision. The ways in which state-level public defense systems achieve those goals are summarized in Appendix A, with some points of interest briefly described here.

To identify noncitizens, about half of states with state-level public defense organizations require attorneys to ask clients a citizenship screening question in their initial conversation with each client.[21] However, defenders report that many clients do not accurately know or report their own immigration status.[22] Additionally, some clients who know their immigration status do not trust their public defenders enough to share it, and may not communicate their status until the final stages of a case.

To try to identify all noncitizens early in case development, some states like Hawaii train attorneys to ask first where each client was born, and then more questions about their immigration to the United States.[23] Using that information, attorneys are then expected to investigate status to provide accurate information.[24] However, other states simply rely on line attorneys’ discretion to identify which clients need Padilla advisals and which do not.[25] This can be an issue because, like the rest of the population, attorneys are subject to stereotypes and misconceptions about immigration and citizenship.[26]

Once noncitizens are identified, their attorney either conducts independent research or consults with an expert to determine immigration consequences of their case. Almost all states with state-level public defense organizations have a state-level structure for the use of experts to provide consultations for line attorneys on Padilla issues.[27] Some states use in-house experts, while others contract with nonprofits or private attorneys.[28] The subject interviewed for this paper generally believed that in-house experts were preferable to external experts, and subjects in several states with external experts were actively seeking funding for in-house experts. In most states, the official policy is that line attorneys should seek an expert consultation for every noncitizen client.[29] However, this is not the case in every state. Iowa has an in-house expert, but the state organization has no official policy requiring line attorneys to seek consultation.[30] In Missouri, there is no structured relationship with experts, and no official policy requiring expert consultation at all.[31]

To share information with experts, many states use forms that line attorneys fill out when they identify noncitizens.[32] Experts use that information to write up a memo about possible consequences and alternatives, and send it back to the line attorney to meet with the client.[33] Some states use very thorough forms to try to get as accurate of information as possible, including questions about the client’s history, mental health, and life experiences.[34] Maryland used to be one such state, until leaders noticed that attorneys were leaving their forms mostly blank.[35] They shortened their form to just seven questions and had their experts address ambiguity and different possibilities in their responses, which they say has significantly increased attorney use of expert services.[36]

The content of basic Padilla advisals seems similar between states, which Eagly noted in her article was also true between different California counties.[37] Regarding timing, experts agree that attorneys should determine citizenship as early as possible in representation to develop mitigating evidence and to help with later immigration-friendly plea negotiations. While most states train attorneys to ask about citizenship in initial interviews, experts report, with some frustration, that line attorneys often wait to reach out until plea negotiations begin or until sentencing is set.[38]

Beyond criminal trials, some public defender offices with robust immigration resources engage in policy work[39] on immigration issues. Massachusetts, for example, has advocated for the Safe Communities Act, which prohibits questioning by police and courts about immigration status, increases protections in immigration enforcement interviews, and prevents law enforcement from initiating contact with the department of homeland security related to the release of an incarcerated person.[40] Other defenders advocate in the legislature to craft criminal statutes in ways that will help avoid immigration consequences, or put out statements opposing legislation to make state sheriffs 278(b) signatories.[41] Public defenders in more liberal states are more likely to report doing policy advocacy on immigration issues.[42] Some experts reported that hostile attitudes towards immigrants in their states limit the possibilities for policy work.[43]

While public defenders are not able to represent clients in immigration proceedings, one expert told me that they also include information in their Padilla memos to help the client in future immigration proceedings where they are likely to be unrepresented.[44] Many of my subjects reported frustration with their inability to support in immigration proceedings.[45] As Iowa’s expert put it, “Even when we do very strong work on the criminal case side, if the client doesn't have informed advocacy in immigration court our work just doesn't always matter.”[46]

3. Major Issues

My research showed significant problems with states’ abilities to identify noncitizen clients, lack of funding for Padilla experts leading to caseload issues, rapidly changing federal law and policy, and an unmet need for networking opportunities between states.

A. Likely Failures to Identify Noncitizens

Preliminary data suggests that states may be failing to identify all clients who should receive Padilla advisals. Most of the in-house immigration experts I spoke with mentioned how challenging it was to make sure line attorneys identified and referred all noncitizen clients for assistance.[47] Eagly noted a similar issue in California, but dedicated little space to its analysis.[48]

While it is not possible to identify the “right” expected number of Padilla advisals per year given the lack of data, some numbers are so low as to strongly indicate a failure to identify and advise some noncitizen clients. Since July 1, 2023, North Dakota’s public defender has provided only 124 Padilla advisals, which amounts to about 67 per year.[49] While North Dakota has a comparatively low foreign-born population,[50] it has a higher foreign-born population than Vermont,[51] where an in-house immigration expert gives 250 Padilla advisals per year.[52] This could be related to the extremely different political landscapes of North Dakota and Vermont,[53] or North Dakota’s dangerously low public defense budget.[54]

Wisconsin and Minnesota are more comparable states where experts still provide vastly different numbers of Padilla advisals. The two states are geographic neighbors and both use in-house experts for Padilla advisals.[55] They also have similar noncitizen demographics: in both states, the most common foreign birthplace is Mexico, with significant populations also born in India, Somalia, and Vietnam.[56] Their offices have similar budgets,[57] and comparable percentages of their populations voted for Trump in 2024.[58]

Despite those similarities, Minnesota provided about ten times more Padilla advisals per year in 2024, when controlling for foreign-born population size. Minnesota’s immigration expert receives about 20-25 referrals per day normally, which amounted to 3,735 in 2024 (this year, she received 3,800 between July 1, 2024 and March 27th, 2025, which annualizes to 5,400).[59] Compared to Minnesota’s foreign-born population of about 500,000 individuals, this is a rate of .007 Padilla advisals per foreign-born resident per year (or .011 at the 2025 rate). Wisconsin, contrastingly, has a foreign-born population of 304,000 individuals, and its two in-house immigration experts assist with about 200 total immigration consults per year.[60] That amounts to just .0007 consults per foreign-born Wisconsin resident per year, or one-seventeenth the number of advisals per foreign-born resident compared to Minnesota.

While it is impossible to identify causation from the type of data used here, the difference between Minnesota’s and Wisconsin’s systems for identifying noncitizens could help explain this difference. Minnesota uses a process embedded in its intake software to ensure that line attorneys screen for potential citizenship issues.[61] Before proceeding to the next step in the intake process, the software requires attorneys to click a box saying whether the client was born in the United States or not.[62] If the answer is no, the attorney must fill out a form with more information that is forwarded to the state’s immigration expert.[63] Minnesota’s public defense leadership emphasizes training line attorneys to screen for citizenship over learning substantive immigration law themselves, citing the complexity of the law and the risk of line attorneys overestimating their own expertise.[64] Minnesota has seen referrals go up significantly since it implemented software requiring attorneys to ask every client where they were born before proceeding.[65] Minnesota is the only state surveyed to use this type of process, and is a high outlier for the number of Padilla advisals it provides per year.[66]

Wisconsin does not require its defenders to ask about birthplace or citizenship in its initial screening process.[67] Staff attorneys have access to a google form which they can fill out and send to the in-house experts to receive information about immigration consequences.[68] Wisconsin’s immigration experts are passionate about their jobs, and take steps like driving to local offices to provide training or even consulting with clients themselves on complex cases.[69] Wisconsin’s public defenders still may be meeting their barebones Padilla obligations by providing consultations without expert advice. However, it is also very possible that they are failing to identify all individuals who need immigration-sensitive defense that they represent.

B. Caseload Issues

As Eagly reported, it is challenging to define an appropriate caseload for an immigration expert.[70] Eagly recommended that full-time experts should not provide more than 1,500 Padilla advisals per year, which would mean spending fifty-eight minutes on average per advisal.[71]

I was able to obtain the number of full-time employees per state in most states with in-house experts, and caseload information for five in-house immigration experts, summarized in Appendix B. The caseloads of in-house attorneys in Vermont and Hawaii are both over Eagly’s recommended caseload cap, because they function as in-house immigration experts while managing full caseloads.[72] Vermont’s criminal immigration expert, Dawn Seibert, manages a full post-conviction caseload in addition to consulting on about 250 Padilla advisals per year.[73] Hawaii similarly uses two line attorneys who manage full caseloads while serving as the state’s immigration experts,[74] which is particularly surprising due to its large foreign-born population.

Of states with in-house experts with time dedicated to Padilla issues, Minnesota, with 3,800 advisals provided so far this year by one immigration expert, and Virginia, with 496 advisals by one expert so far this year, were both other Eagly’s recommended maximum cap of 1,500 advisals per expert per full-time employee year.[75]

C. The New Immigration Landscape

The law of immigration is changing rapidly under the second Trump administration,[76] and public defenders are struggling to stay up to date with the consequences of those changes for their clients.[77] Several public defenders reported increased contact between law enforcement and immigrant populations.[78] Others report prosecutors pursuing immigration consequences of their clients more frequently than before. One defender in a very liberal state shared that prosecutors were more willing to negotiate with public defenders than before due to their own liberal leanings. Almost all defenders I spoke with reported increased ICE presence in courthouses.

Well-resourced state-level public defense organizations communicate information about these changes to line attorneys through trainings and email updates. In-house immigration experts, who typically share this information, struggle to stay informed themselves due to very limited funds for the experts to attend any external trainings.

D. The Need for Training and Networking Opportunities

Immigration experts at public defender offices are hungry for immigration-specific training and the opportunity to meet with their counterparts. Currently, no organization convenes public defense immigration experts across the country, and few experts have contact outside of their regions. At least one group, consisting of in-house immigration experts in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., meets to discuss updates to immigration law and enforcement, and issues arising in their work.[79] Participants call the meetings invaluable, and say they do not know how people do the job without them.[80]

Networking and training could help public defenders discuss and resolve common questions and determine best practices. For example, public defenders vary significantly in their attitude towards tracking data on representation of noncitizens.[81] Despite the protection of attorney-client privilege, some experts are more cautious than others about tracking citizenship information in case management software. Discussing the issue between offices, no matter the resolution, could help defenders identify benefits and risks for their clients. Networking opportunities could also help bring best practices and new ideas to light, such as Minnesota’s screening system or Maryland’s seven question form.[82]

Conclusion

Most state-level public defender organizations have some form of structure to ensure that their attorneys meet Padilla’s mandate. However, the defense community still needs more resources and information to provide robust representation to noncitizens accused of crimes. Future research should collect and compare more numerical data, such as advisals per year and case outcomes, to provide more insight into effective practices for finding and helping noncitizens in criminal cases. Future research should also survey private criminal defense attorneys, who some experts suggest may provide less immigration-sensitive representation than public defenders on average.[83]

Padilla is not a solution to the racism,[84] lawlessness,[85] and inhumane confinement[86] that characterize the intersection of criminal law and immigration in the United States. However, it is a critical floor for effective representation of noncitizens in criminal matters. Most public defenders I spoke with for this paper were deeply passionate about representing noncitizens, and said they fought harder and filed more motions when they knew deportation was on the table for a client.[87] Still, with limited resources and laws stacked against noncitizen clients, attorneys struggle with feelings of helplessness and despair.[88] In the words of Vermont’s in-state expert, who has a full caseload and manages the state’s Padilla consultations often on the weekends, “It’s kind of overwhelming. I do as much as I can.”[89]

[1] 559 U.S. 356, 374 (2010).

[2] Id. at 366.

[3] Margaret Colgate Love & Gabriel J. Chin, Padilla v. Kentucky: The Right to Counsel and the Collateral Consequences of Conviction, Champion, May 2010, at 19.

[4] McGregor Smyth, The Seismic Evolution of Padilla v. Kentucky and Its Impact on Penalties Beyond Deportation, 54 Howard Law Journal 795, 798 (2011).

[5] Question asked to Professor García Hernández, March 4, 2025.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963).

[9] Eve Brensike Primus, The Problematic Structure of Indigent Defense Delivery, 122 Mich. L. Rev. 207, 211.

[10] Primus, supra, at Appendix A. The states that organize public defense entirely at the state level are Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. The states that organize public defense at the state level other than for municipal ordinances are Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, and Rhode Island. I opted to include the second set of states because municipal ordinances are unlikely to lead to immigration consequences.

[11] California has more robust state-law protections of noncitizens than most states, including its sanctuary law and a law allowing noncitizens to have California drivers’ licenses. See California Senate Bill 54 (2017) (protecting state and local resources from use for federal immigration enforcement); California Assembly Bill 60 (2013) (allowing noncitizens to have drivers’ licenses).

[12] See Appendix A.

[13] See Appendix B.

[14] Id.

[15] See Eagly, supra, at 79 (describing qualitative interview strategies).

[16] Those states were Arkansas, Delaware, and Montana. Despite calling and emailing at least six people per state in each state, I was not able to reach anyone who would speak with me.

[17] See generally 2020 Census Results, United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/2020-census-results.html.

[18] This statement assumes that the government will not revoke citizenship or deport U.S. citizens for criminal charges. However, the current administration seems poised to do so. See Brian Mann, ‘Homegrowns are Next’: Trump Hopes to Deport and Jail U.S. Citizens Abroad, NPR (April 16, 2025), https://www.npr.org/2025/04/16/nx-s1-5366178/trump-deport-jail-u-s-citizens-homegrowns-el-salvador. Such a change could significantly increase the need for Padilla advisals.

[19] See Ming Hsu Chen, The Political (Mis)Representation of Immigrants in the Census, 96 N.Y.U L. Rev. 901, 917 (2021).

[20] See Jennifer M. Chacón, “Crimmigration”: race, and Critical Race Theory in the United States in Handbook on Border Criminology 45 (edited by Maggy Lee et al., 2024).

[21] See Appendix A.

[22] Phone call with anonymous public defender in New Mexico (May 8, 2025) (notes on file with author). The attorney explained that some clients believe that they have naturalized when they have not, or are unaware of expired visas.

[23] Interview with Hayley Cheng, Assistant Public Defender for the state of Hawaii (April 8, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[24] Id.

[25] See Missouri State Public Defender Guidelines for Representation at 40 (May 2021); email with Greg Mermelstein, Deputy Public Defender (March 27, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[26] For example, one public defender I spoke with expressed an understanding that Padilla advisals are only necessary for undocumented clients. For a study on factors that influence perceptions of illegality, see René D. Flores & Ariela Schachter, Examining Americans’ Stereotypes about Immigrant Illegality, 18 Contexts 2 (2019) (finding that survey respondents used inaccurate stereotypes to assess whether people were in the United States legally.)

[27] See Appendix A. One outlier is Connecticut, where line attorneys reference a comprehensive guide to the immigration consequences of all state statutes and only consult with experts if the answer is not apparent from that guide. Interview with Andrew O’Shea, Director of Training for Connecticut Public Defenders (April 1, 2025) (notes on file with author). The guide was created by Yale students seven years ago, but the organizations involved have “washed their hands of it” and are unwilling to update the guide. Line attorneys only reach out to experts when the guide does not provide an adequate answer.

[28] See Appendix A.

[29] See Appendix A.

[30] Email from Julia Zalenski, an Assistant Public Defender who runs Iowa State Public Defender’s crimmigration program (March 27, 2025) (on file with author).

[31] See Missouri State Public Defender Guidelines for Representation at 40 (May 2021); email with Greg Mermelstein, Deputy Public Defender (March 27, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[32] See, e.g., interview with an anonymous attorney for the New Hampshire Public Defender (April 3, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[33] Id.

[34] Interview with Ashley Warmeling (May 5, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[35] Interview with Stephanie Wolf, Director of Immigration Services for the Maryland Office of the Public Defender (April 29, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[36] Id.

[37] Eagly, supra, at 51.

[38] Email from Julia Zalenski, an Assistant Public Defender who runs Iowa State Public Defender’s crimmigration program (March 27, 2025) (on file with author).

[39] Movement lawyers believe that “the best defense for our clients will often require [attorneys] to go beyond traditional courtroom strategies and to work in ways that support the broader movement for immigration justice.” Movement Lawyering in Immigration Defense Presentation at slide 5 (Feb. 18, 2025). For example, San Francisco Public Defender, a well-resourced office focused on holistic representation, advocates in public campaigns and policy advocacy on immigration issues, including work to shut down detention facilities to reduce ICE capacity. Id. at slides 11 and 12. By engaging in client-centered advocacy beyond criminal trials, the office is able to secure better results for their noncitizen clients.

[40] Interview with CPCS Staff (April 30, 2025); Safe Communities Act, Massachusetts Immigrant & Refugee Advocacy Coalition (Feb. 3, 2025), https://miracoalition.org/news... (explaining the Act).

[41] Interview notes on file with the author (some PDs wished to speak anonymously on certain issues).

[42] See Appendix A.

[43] Source anonymous for privacy.

[44] Source anonymous for privacy.

[45] See, e.g., email from Julia Zalenski, an Assistant Public Defender who runs Iowa State Public Defender’s crimmigration program (March 27, 2025) (on file with author).

[46] Id.

[47] See, e.g., interview with Dawn Seibert (March 31, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[48] Eagly et al., supra, at 55.

[49] Interview with Todd Ewell (April 1, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[50] See Appendix B, using data from Census.gov.

[51] Id.

[52] Interview with Dawn Seibert (March 31, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[53] Sixty-eight percent of North Dakota voters voted for Donald Trump in 2024, for example, compared to only 33 percent of Vermont voters. Presidential Election Result: Trump Wins, The New York Times (March 4, 2025) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/11/05/us/elections/results-president.html.

[54] North Dakota’s public defense budget is so low that the Commission itself is publicly implying that its system may not pass constitutional challenge. SB 2022, Senate Appropriations Report, Government Operations Division (January 13, 2025), https://ndlegis.gov/assembly/69-2025/testimony/SAPPGOV-2022-20250113-28525-F-FINCK_TRAVIS_W.pdf.

[55] Interview with Kate Drury, one of two immigration practice coordinators for the State Public Defender Administration in Wisconsin (April 2, 2025) (notes on file with author); interview with William Ward, State Public Defender for Minnesota (March 27, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[56] See David Long et al., Wisconsin’s Foreign Born Population, Applied Population Lab, https://apl.wisc.edu/data-brie...; Foreign Born Population by Birthplace, Minnesota Compass, http://mncompass.org/chart/k264/population-trends#1-5581-g.

[57] Minnesota spent $124 million on public defense in 2024, while Wisconsin spent $127 million. See About Us, Minnesota Board of Public Defense, https://www.pubdef.state.mn.us...; State of Wisconsin Public Defender Board, Agency Budget Request 2025-2027 at 7, https://doa.wi.gov/budget/SBO/2025-27%20550%20SPD%20Budget%20RequestNR.pdf.

[58] Fifty percent of voters in Wisconsin picked Trump, compared to 47 percent in Minnesota. Presidential Election Result: Trump Wins, The New York Times (March 4, 2025) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/11/05/us/elections/results-president.html.

[59] Interview with Kate Drury (April 2, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[60] Interview with William Ward, State Public Defender for Minnesota (March 27, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

[63] Id.

[64] Id.

[65] Id.

[66] See Appendix B.

[67] Interview with Kate Drury (April 2, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[68] Id.

[69] Id.

[70] Id. at 64.

[71] Id.

[72] Interview with Hayley Cheng, Assistant Public Defender for the state of Hawaii (April 8, 2025) (notes on file with author); interview with Dawn Seibert (March 31, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[73] Interview with Dawn Seibert (March 31, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[74] Interview with Hayley Cheng, Assistant Public Defender for the state of Hawaii (April 8, 2025) (notes on file with author); Appendix B.

[75] Appendix B.

[76] See, e.g., The White House, Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of the United States by Tren de Aragua, WhiteHouse.gov, https://www.whitehouse.gov/pre... (explaining the President’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act, resulting in significantly reduced due process protections for some noncitizens.)

[77] Email from Darcy Fisher (May 14, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[78] Anonymous sources for privacy regarding all actions of the federal government. An attorney told me she was seeing such as increased stops for traffic violations “in hopes of getting people into the ICE pipeline.” She also said that police were proactively calling ICE, which was a new practice in her experience.

[79] Interview with Ashley Warmeling (May 5, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[80] Id.

[81] Minnesota tracks birthplace information in its case management software. Interview with William Ward (notes on file with author). Many other states use google forms and email memos for experts and line attorneys to communicate about client immigration status. However, some states, like Connecticut, do not track client immigration status. Interview with Andrew O’Shea, Director of Training, Office of the Chief Public Defender (notes on file with author). One expert, who asked to remain anonymous, explained that tracking client status creates a risk of that information being accessed to deport clients.

[82] Interview with William Ward (March 27, 2025) (notes on file with author); interview with Stephanie Wolf (April 29, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[83] Lecture by Professor García Hernández, March 4, 2025.

[84] Adrian Florido, ‘Antagonized for Being Hispanic’: Growing Claims of Racial Profiling in LA Raids, Jul. 4, 2025, N.P.R., https://www.npr.org/2025/07/04/nx-s1-5438396/antagonized-for-being-hispanic-growing-claims-of-racial-profiling-in-la-raids.

[85] Ko Lyn Cheang, This Man is a U.S. Citizen by Birth. Why Did ICE Mark Him for Deportation-Again?, Jul. 25, 2025, S.F. Chron., https://www.sfchronicle.com/us-world/article/deport-citizen-immigration-ice-20774259.php.

[86] Complaint Exposes Torture and Cruel and Degrading Treatment at Louisiana Immigration Detention Center, Jan. 8, 2025, Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, https://rfkhumanrights.org/our-voices/complaint-exposes-torture-and-cruel-and-degrading-treatment-at-louisiana-immigration-detention-center/.

[87] See, e.g., phone call with anonymous public defender in New Mexico (May 8, 2025) (notes on file with author).

[88] Id.

[89] Interview with Dawn Seibert (March 31, 2025) (notes on file with author).