Blog

Hashing it Out: How an Automated Crackdown on Child Pornography is Shaping the Fourth Amendment

Content Warning: This article discusses child sexual abuse material, and contains information that readers may find disturbing.

The risk of unwanted exposure is something the modern American has to expect. For instance, a Google Street View car could be lurking around any corner, poised to catch you doing something crazy, strange, or embarrassing. However, Google has caught people doing much worse than picking their nose on the sidewalk.

On July 9, 2015, William Miller attached two images depicting the sexual abuse of children to an email on his Gmail account. Three years later, Miller was convicted for distributing child pornography and sentenced to twelve and a half years in federal prison. Like a growing number of sex offenders, Miller was caught because Google’s algorithms were watching.

The Fourth Amendment only applies to government searches, and under an age-old rule, the government may use the fruits of private searches in investigations and prosecutions, no matter how unreasonable those searches are. However, the “Private Search Doctrine” was forged in an era where private searches were largely case-specific and human-performed. The world has changed, and Google and other companies increasingly use automated systems to monitor all of their users for illegal activity. In 2018, Chief Justice John Roberts acknowledged that modern corporations are not typical witnesses, and “they are ever alert, and their memory is nearly infallible.”

The internet has enabled an unprecedented rise in the availability of child pornography, and the removal of online child pornography and prosecution of its distributors is sorely needed. Courts have been happy to ratify extensive digital inspections performed by private companies like Google. However, there are reasons to be cautious. The surveillance technology that put Miller in prison is systematized and ubiquitous, and the government has easy, constitutional, and in the case of child sexual abuse, mandatory access to its output. In its present state, the private search doctrine is broader than it has ever been. It is time to consider whether the benefits are worth the risks.

The Google Search Engine

Unbeknownst to Miller, as soon as they were attached to the email, his files passed through a “hashing” checkpoint. A “hash” is a string of numbers that correspond with a digital file. Hashes are based on a file’s unique properties, so two files of the same image would have the same hash. However, if the second file differs by as little as one pixel, it would yield a different hash. Because hashes describe a file’s properties, they can be used like fingerprints to identify files by their unique characteristics. Hashing technology, developed in the late 2000s, has become ubiquitous in the tech industry as a cheap and reliable way to screen for illegal content.

Google subjects all files uploaded to its platforms to a two-part process. First, Google scans the file’s properties and generates a hash. Second, Google compares this to a list of hashes that correspond with known child pornography. If they find a match, it means that the uploaded file is identical to an image that a Google employee has reviewed and confirmed to be apparent child pornography.

Google’s hashing checkpoints are not required by law. Google has both moral and commercial reasons to screen for child pornography. However, as soon as its checkpoint flagged Miller’s files, Google had a legal duty to do something about it.

18 U.S.C. § 2258A requires Google and similar services to report any child pornography they detect with a “cybertip” containing information identifying the account user. These reports are sent to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), a non-profit charged by section 2258A with processing them.

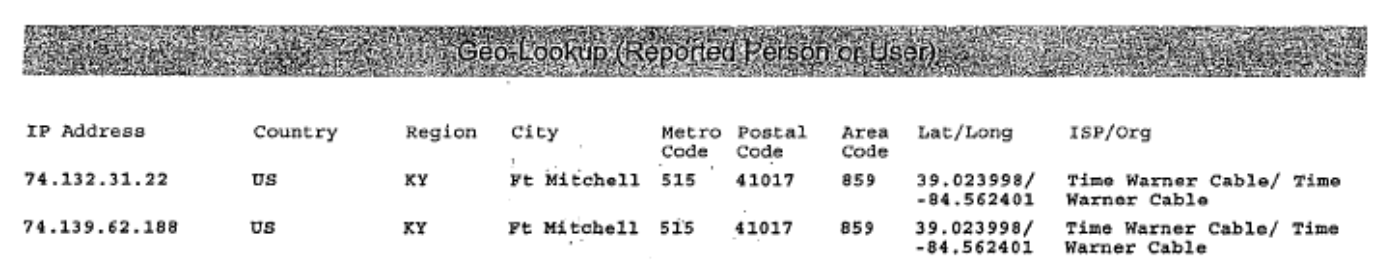

Section of NCMEC Report Detailing Miller’s Location Information

While Google sometimes reviews a cybertip before submitting it, in most cases, including Miller’s, the tip is sent automatically. This means that though the hash value of the files matched images that a Google employee had previously confirmed as illicit, no one at Google looked at the images attached to Miller’s email before they landed at NCMEC. A worker at NCMEC conducted a deeper investigation, tracing Miller’s public online presence to supplement the information provided by Google and further develop the report. Like Google, NCMEC did not open Miller’s files.

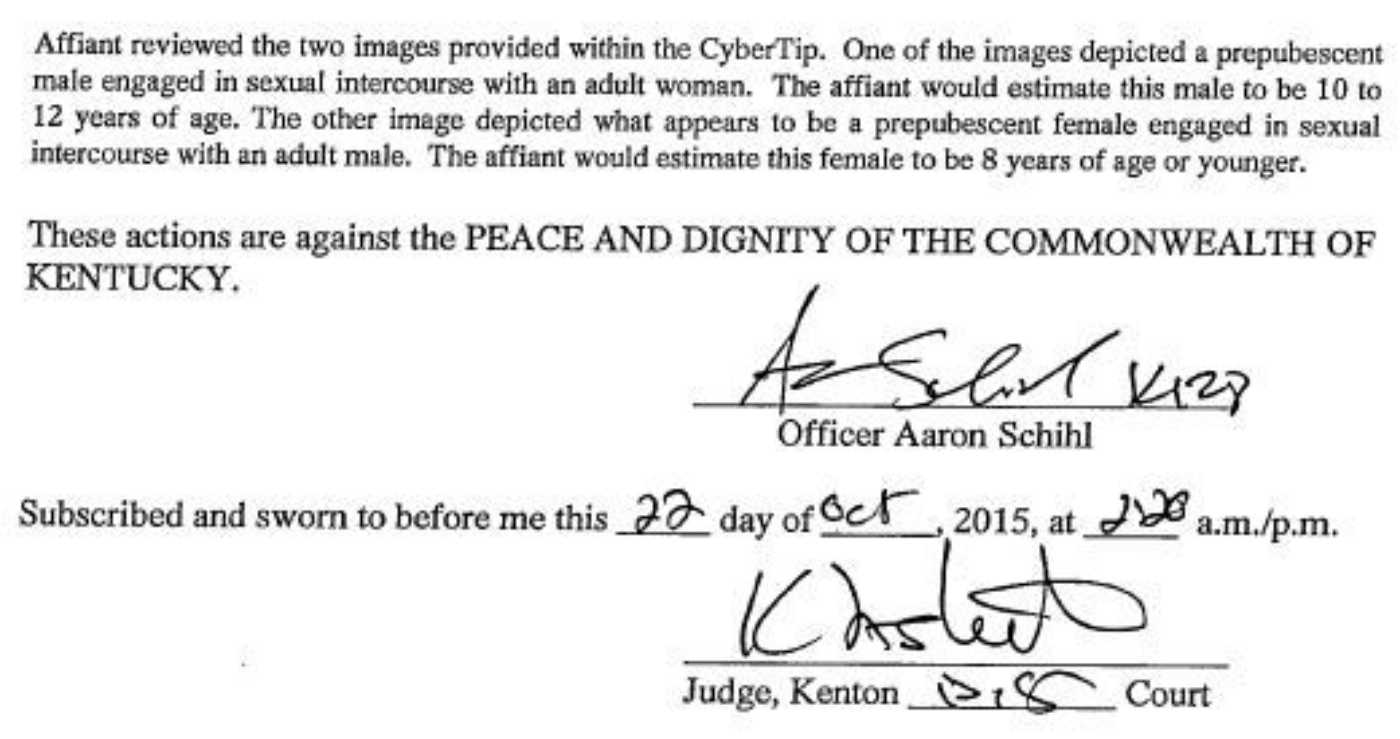

On August 13, 2015, a little over a month after the files were attached, the cybertip reached law enforcement. Detective Schihl of the Kenton County Police Department was the first person to open and review Millers’ files to confirm their content. It was also at this point that Miller’s Fourth Amendment rights kicked in. Though a subpoena to Miller’s internet service provider sufficed to obtain his address, the government obtained a warrant to search Miller’s Gmail account. Armed with the cybertip, Detective Schihl had no trouble doing so.

Taken from an Affidavit in Support of a Warrant to Search Miller’s Gmail Account

Based on that search, which revealed more incriminating emails, the government obtained another warrant to search Miller’s house, and yet another to search the devices and hard drives that the premises search yielded.

On November 17, 2016–a little over a year after the images were uploaded–Miller was indicted on six counts related to child pornography. At trial, the government introduced the cybertip. It also introduced emails provided by Google, subscriber information from Miller’s ISP, and Skype messages from a search of Miller’s devices. The government’s case was enabled entirely by Google’s hash match, but the evidence against Miller was overwhelming. He was convicted and sentenced to 150 months in federal prison.

The Private Search Doctrine

The Fourth Amendment protects areas where a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy from government search; in Miller’s case, this meant the government needed a warrant to search his emails. However, thanks to the private search doctrine, Google is not bound by the same rules.

The logic of the private search doctrine is simple: the Fourth Amendment only applies to government action, so if a private party conducts an unreasonable search, there has been no government search, and so there is no Fourth Amendment violation. Nonetheless, once a private search has been executed, any continuing expectation of privacy as to the searched items is deemed unreasonable. As such, the government may review the results of a private search as long as it does not exceed the search’s scope.

However, the private search doctrine is not limitless. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable government searches, not just searches by government officials. This means that a search by a private party is unconstitutional when it is nonetheless “fairly attributable” to the government. For instance, in U.S. v. Reed, the Ninth Circuit found a search of a motel room by the motel manager unconstitutional when two police officers stood by as lookouts, thereby “indirectly encourag[ing]” the search even if they did not instigate it or enter the room themselves.

The private search doctrine was most recently addressed by the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Jacobsen, where FedEx employees inspecting a damaged package noticed a suspicious white powder and notified the police. The police tested the powder and identified it as cocaine. In Jacobsen, the drug test did not exceed the FedEx inspection because whether it returned a positive or negative result, it did not compromise any legitimate interest in privacy: there is no legitimate private interest in having cocaine, and instead of revealing any private fact, a negative test could only show that the powder was not cocaine.

Miller’s Appeal

Miller promptly appealed his conviction to the Sixth Circuit with two arguments. First, Miller argued that Google conducted an unreasonable search fairly attributable to the government when it scanned his files. Second, he argued that Detective Schihl conducted an unreasonable search when he opened and viewed the files that Google had sent through NCMEC.

The Sixth Circuit found that Google’s search was not fairly attributable to the government, pointing out that the decision to use hash scans was entirely Google’s choice, and it was only after it found child sex abuse images that it came under legal duty to file a report. Delineating a duty to perform a search from a duty to report its contents, the court found that the Fourth Amendment only governed the former. Since the decision to conduct the search was entirely Google’s, the Fourth had nothing to say about it.

The court also held that Detective Schihl had not gone beyond the scope of Google’s search by laying eyes on the contents of the files themselves. The court noted that Schihl could have learned “no more” about the files by opening and viewing them than Google had learned through its hash match. Even if Miller’s cybertip was automatically sent, the illegal images had to have been previously viewed by Google employees in order to be added to the list of illicit images that Miller’s files were compared against. Schihl learned no more than Google already knew. As such, while independently viewing the files would have invaded a “legitimate privacy interest,” Detective Schihl’s search was legal because “Google’s actions had already frustrated the privacy interest in the files.”

While it began by noting its place in a shifting world of new technologies, the Sixth Circuit’s opinion in Miller barely touched on the novelty posed by the ubiquity of hashing scans. Unlike the Fedex agents in Jacobsen, Google is not searching a single damaged package. Instead, hashing scans subject everybody’s files to the same scrutiny. Although Google erects these checkpoints voluntarily, their purpose is inherently intertwined with a legal requirement to report its results to authorities. With cases like Miller’s, courts apply the private search doctrine in a context where it has never been before.

Why Does This Matter?

With U.S. v. Miller, the Sixth Circuit joined a growing number of jurisdictions to issue similar opinions, ratifying the constitutionality of the government’s growing reliance on hashing technology to catch sex offenders.

In the context of child pornography, the reach of hashing technology and the willingness of the courts to ratify it are undeniably good things. Survivors of childhood sexual victimization shoulder the burden of their experience well into adulthood, and the persistence of images that commemorate their abuse perpetuates both their trauma, and the toxic cycle of child abuse. The meteoric growth of the internet has also seen meteoric growth in the accessibility of child pornography, and companies that actively fight this surge should be commended.

Despite this, unreserved application of the private search doctrine to systematized private searches comes with risk.

The central novelty of hash-scanning is its ubiquity. Google scans all files that pass through its platforms, affecting over a billion users. Despite its automation, Google’s hash matching system remains susceptible to human error. For instance, a Google employee could mistakenly add an innocent image to Google’s library of illicit hashes, exposing anyone who sends that image over Gmail to police scrutiny. The risk is augmented if the hash is added to an industry-wide database instead of a company specific one.

Significantly, unlike the drug test in Jacobsen, which could only reveal that a substance was or was not cocaine, a visual inspection of a false match by a police officer necessarily goes beyond confirming that the image is not child pornography, actually revealing the contents to the government’s eyes, no matter how private it is.

Furthermore, there is the risk that a company will choose to scan and report other, less heinous, digital contraband. Google already scans for pirated media on at least some of its programs, though they do not yet appear to report digital pirates to the police. Also worrying is Silicon Valley’s track record of vindictiveness, aggressiveness, and dirty tricks. Hashing technology’s potential use to involve the government in competitive or personal disputes should be taken seriously.

Finally, there is the deeper question of what the Fourth Amendment should protect. By its text, the Fourth Amendment only protects “persons, houses, papers, and effects.” The extension of the Amendment to a reasonable expectation of privacy was itself a response to new technology. In his dissent in Olmstead v. U.S. which is considered fundamental to the modern right to privacy, Justice Brandeis said of then-novel wiretapping technology: “Subtler and more far-reaching means of invading privacy have become available to the government…the progress of science in furnishing the Government with means of espionage is not likely to stop with wiretapping.” Google is not a government entity, but its hashing technology has given the government an omnipresent informant. It indirectly provides the government with “subtler and far-reaching” tools of criminal investigation precisely because of its private posture. Is this a constitutionally permissible situation?

Conclusion

On March 1, 2021, Miller petitioned the Supreme Court to hear his case. Addressing the private search doctrine’s role in the internet era will not be easy. The Court must balance a surge in cybercrime with the Fourth Amendment’s guarantee of privacy from unreasonable government scrutiny. Nonetheless, the new ubiquity of systematized private searches needs addressing. Whether the Supreme Court accepts the reasoning of the Sixth Circuit or limits the private search doctrine, the Fourth Amendment will be changed for decades to come.