Blog

California’s War On Weed Rages Post-Legalization

Photo by Janko Ferlić via Unsplash

Proposition 64 made four promises to California voters in 2016: (1) legalize adult, non-medical cannabis use, (2) create a regulatory system for non-medical cannabis businesses, (3) impose taxes on cannabis, and (4) change penalties for cannabis-related crimes. Almost five years since California issued its first state licenses, consumers aged 21 and older are able to purchase cannabis from businesses that are licensed, regulated, and taxed by state and local agencies. California has collected over $4 billion in cannabis tax revenue. Prop. 64 reduced penalties for cultivation, possession, and distribution to misdemeanors, while the Medicinal and Adult-Use Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MAUCRSA) of 2017 established the state’s cannabis regulatory system with civil penalties.[1]

Yet cannabis possession, use, and distribution remains not only federally illegal, commercial cultivation without a license remains a crime under state law as well. Legalization brought changes to California’s Medical Marijuana Program, extending criminal liability to medical collectives and cooperatives in the process. Meanwhile, state and federal law enforcement efforts to combat cannabis in California are more inextricably linked today than in the years prior to legalization. In 2021, half of the cannabis sites eradicated by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) nationwide were in California, along with 86% and 87% of the plants and dried cannabis destroyed nationally, and 86% of the weapons seized that year. In October 2022, the California Department of Justice announced that the state’s Campaign Against Marijuana Planting (CAMP) is transitioning from a 13-week annual effort to a year-round Eradication and Prevention of Illicit Cannabis (EPIC) task force. At the same time that state and local equity programs aim to assist cannabis businesses “disproportionately or negatively impacted by the War on Drugs,” some jurisdictions have defined this in part, as residing near an eradication. Despite the reduction in criminal penalties and the creation of civil authorities, law enforcement remains at the forefront of cannabis legalization in California.

Background

As a Schedule I Drug under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), cannabis, or “marihuana” as it appears in the statute, is not federally recognized as having any acceptable use.[2] Criminal offenses ranging from simple possession to the manufacture, distribution, or possession with intent to distribute 1,000 or more plants prohibit cannabis possession or use in any quantity.[3] [4] But in 1996, California voters passed Proposition 215, which allowed the possession and cultivation of medical cannabis for certain patients. In the years that followed, the U.S. Supreme Court twice upheld the federal government’s authority to enforce CSA provisions related to cannabis in California even after Prop. 215’s passage.[5]

Despite its victories, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) responded to the rising tide of state legislation and initiatives decriminalizing or legalizing cannabis with a series of memoranda. Most notably in 2013, U.S. Deputy Attorney General James Cole issued his “Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement,” commonly known as the “Cole Memo.” While pledging continued commitment to enforcing the CSA, the Cole Memo expressed a focus for the DOJ’s “limited investigative and prosecutorial resources” on eight priorities. The eight enforcement priorities ranged from prohibiting cannabis sales to minors and “drugged driving,” to environmental and public land concerns, as well as preventing interstate cannabis sales and any associated illegal, violent, and/or organized crime. “Outside of these enforcement priorities,” the Cole Memo continued, “the federal government has traditionally relied on states and local law enforcement agencies to address marijuana activity through enforcement of their own narcotics laws.” The implication was that states could significantly reduce the risk of federal intervention in their legalization efforts by crafting legislation that addressed the eight enforcement priorities. When California voters approved Prop. 64 in 2016, the Cole Memo’s priorities were baked into the initiative.

The Domestic Cannabis Eradication/Suppression Program

But the federal government has hardly left California to its own devices in the years since the Cole Memo. The DEA’s Domestic Cannabis Eradication/Suppression Program (DCE/SP) maintains an on-going sponsorship of state and local law enforcement efforts to eradicate cannabis, including in CA. A 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report defines these eradications as “the seizure and destruction” of cannabis plants and processed cannabis—smokeable [sic] dry, loose, or packaged cannabis, as well as the seizure of weapons and assets, and “apprehension of individuals at the grow site.” Eradications may also remove trash and cultivation infrastructure, such as irrigation tubing and propane tanks. The same year as the GAO report, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded the Cole Memo altogether.

The GAO report details how DCE/SP advances funds to participating states, including California, from the DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture Fund. Participating states and agencies must justify how DCE/SP funds will be used to address illegal cannabis cultivation within their jurisdictions, sign an agreement to eradicate illegal cannabis as a part of DCE/SP, and report information on their eradication and suppression activities to the DEA. From 2015 through 2018, an average of $17.7 million per year was allocated for DCE/SP funding. Even after legalizing cannabis, California has received an outsized share of these funds – between 24-26% of the nationwide total. About two-fifths (39-46%) of the DCE/SP funds distributed to law enforcement went to overtime pay, and another 38-43% was spent on aviation support, such as helicopters. The California Department of Justice’s Campaign Against Marijuana Planting (CAMP) told GAO that helicopters enable it to survey landscapes for illicit cannabis cultivation, transport personnel to and from these remote areas, as well as aid in the removal of cannabis plants. California officials further explained that they navigate legalization in the state by eradicating sites in violation of state and local law.

2011 to 2021: Cannabis Eradication Trends in California

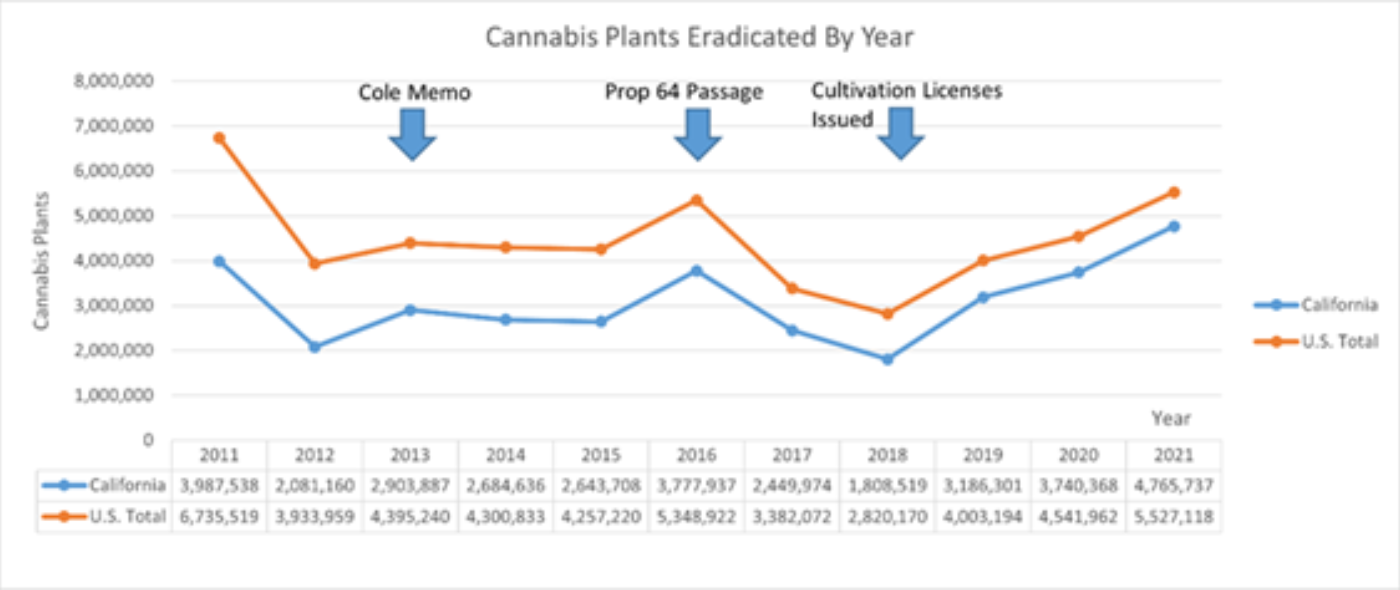

Prop. 64 reduced penalties under state law for cannabis cultivation, possession for sale, and transportation or sale of cannabis from felonies to misdemeanors in the absence of any enhancements.[6] If reductions in criminal penalties and establishment of a regulatory system with civil penalties was intended to transition cannabis away from law enforcement, it has yet to succeed. California law enforcement agencies receiving DCE/SP grants eradicated 4,765,737 cannabis plants in 2021 – 987,800 more than in 2016, the year of Prop. 64’s passage, and 778,199 plants more than a decade ago. Year after year, California law enforcement agencies make up the vast majority of DCE/SP’s nationwide results. From 2011 to 2015, plants eradicated in California represented 52-66% of DCE/SP’s nationwide plant total, but climbed to 80-86% of the plants eradicated across the country over the past three years.

Figure 1 – California & U.S. Total Cannabis Plant Count from the DCE/SP's Previous Year Statistics 2011-2021. DCE/SP’s Total Cultivated Plants Outdoor & Total Cultivated Plants Indoor categories are reflected as a combined total. DEA. 11 July, 2018. Domestic Cannabis Suppression / Eradication Program. Retrieved from https://www.dea.gov/operations... on 7 October, 2022

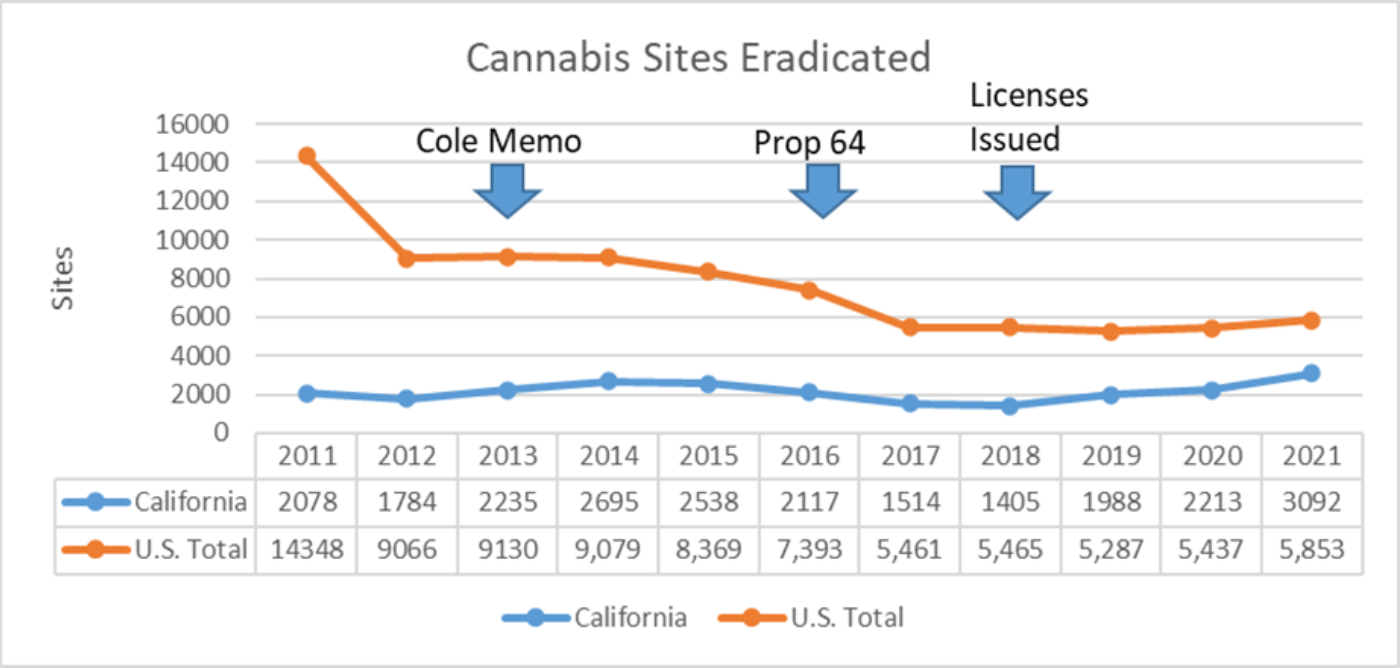

California also saw a 10-year high in the number of cannabis cultivation sites–3,092 sites–eradicated in 2021. That’s 397 more sites than the next highest year, 2014, and 1,014 sites more than in 2011. While the number of sites eradicated nationally has dropped to less than half of the amount eradicated a decade ago, DCE/SP-sponsored efforts by California law enforcement agencies have steadily ramped up since 2018. In 2011, California represented only 14% of the sites eradicated nationally, but by 2021, 52.8% of all DCE/SP eradications occurred in California. California’s processed cannabis seizures also accounted for 87% of DCE/SP’s nationwide total in 2021 (647,035 pounds out of 743,920 pounds), the highest amount reported in the past 10 years. Additionally, 86% of DCE/SP’s reported weapons seizures came from California in 2021 (8,908 out of 10,375), as well as 38% of the value of assets seized ($38,994,307.14 out of $103,774,386.79) and 60% of arrests (3,988 out of 6,606).

Figure 2 - California & U.S. Total Cannabis Sites Eradicated compiled from the DCE/SP's Previous Year Statistics 2011-2021. DCE/SP's Total Eradicated Indoor & Outdoor Sites categories are reflected as a combined total. DEA. 11 July, 2018. Domestic Cannabis Suppression / Eradication Program. Retrieved from https://www.dea.gov/operations... on 7 October, 2022

But DCE/SP is just one aspect of California’s post-legalization cannabis eradication efforts. The California Attorney General’s Office reported that CAMP eradicated between 614,267 plants in 2018 and 1,198,599 plants in 2021. This would account for 25.1%-33.9% of California’s DCE/SP-eradicated plant total over the past four years. In 2019, CAMP eradicated 953,459 plants, while the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) eradicated 12.5 million cannabis plants the same year. CDFW’s eradicated plant total alone is almost four times greater than California’s DCE/SP total for 2019 (3,186,301 plants), and three times greater than the DEA’s nationwide total for plants eradicated that year (4,003,194 plants). Since many state and local agencies participating in DCE/SP do not publically release annual eradication statistics, the total quantities of plants or sites eradicated statewide each year is unknown. Yet the quantity reported by CDFW in 2019 demonstrates that eradication efforts by California law enforcement agencies can exceed those supported by the DEA.

Often emphasized by law enforcement and government officials when touting eradication programs is the environmental damage from illegal cannabis cultivation sites on federal public lands. But information from federal and state agencies indicates that these highly publicized efforts make up only a fraction of eradications. The 2018 GAO report states that “almost 3 million illegal marijuana plants were eradicated from national forests from 2014 through fiscal year 2016” and that 80% of illegal cannabis cultivation on federal land occurs on national forests. From this, GAO concluded that “a significant amount of illegal marijuana eradication takes place on national forests.” But during the same time period, DCE/SP-backed efforts eradicated 13,906,975 plants nationwide, making national forest eradications only 22% of the total plants destroyed and federal land eradications approximately 25% of the total.

CAMP similarly emphasizes that “Drug trafficking organizations utilize Californians [sic] public lands to produce marijuana….” Citing CAMP, CDFW states that 80% of unlicensed cultivation occurred on public lands in 2018, a rate far higher than the federal statistic of 22-25% between 2014 and 2016. Yet even CDFW reports that by 2021, less than 30% of unlicensed cultivation activity in California was occurring on public lands. Environmental enhancements available under Cal. Health & Safety Code § 11358 may provide additional incentive for state and local agencies to focus on environmental-related issues during eradications. Under the Prop. 64-revised statute, any of the fourteen enumerated violations of Fish & Game Code, Water Code, Health & Safety Code, or Penal Code serve as felony enhancements for unlicensed cannabis cultivation.[7] Reducing environmental damage and preventing trespass on federal public lands are long standing purposes of eradication programs. But the highly publicized eradications on public lands appear to constitute around 25% of eradications, and although significant, indicates that the majority of eradications occur on private property.

A License To “Go Legal”

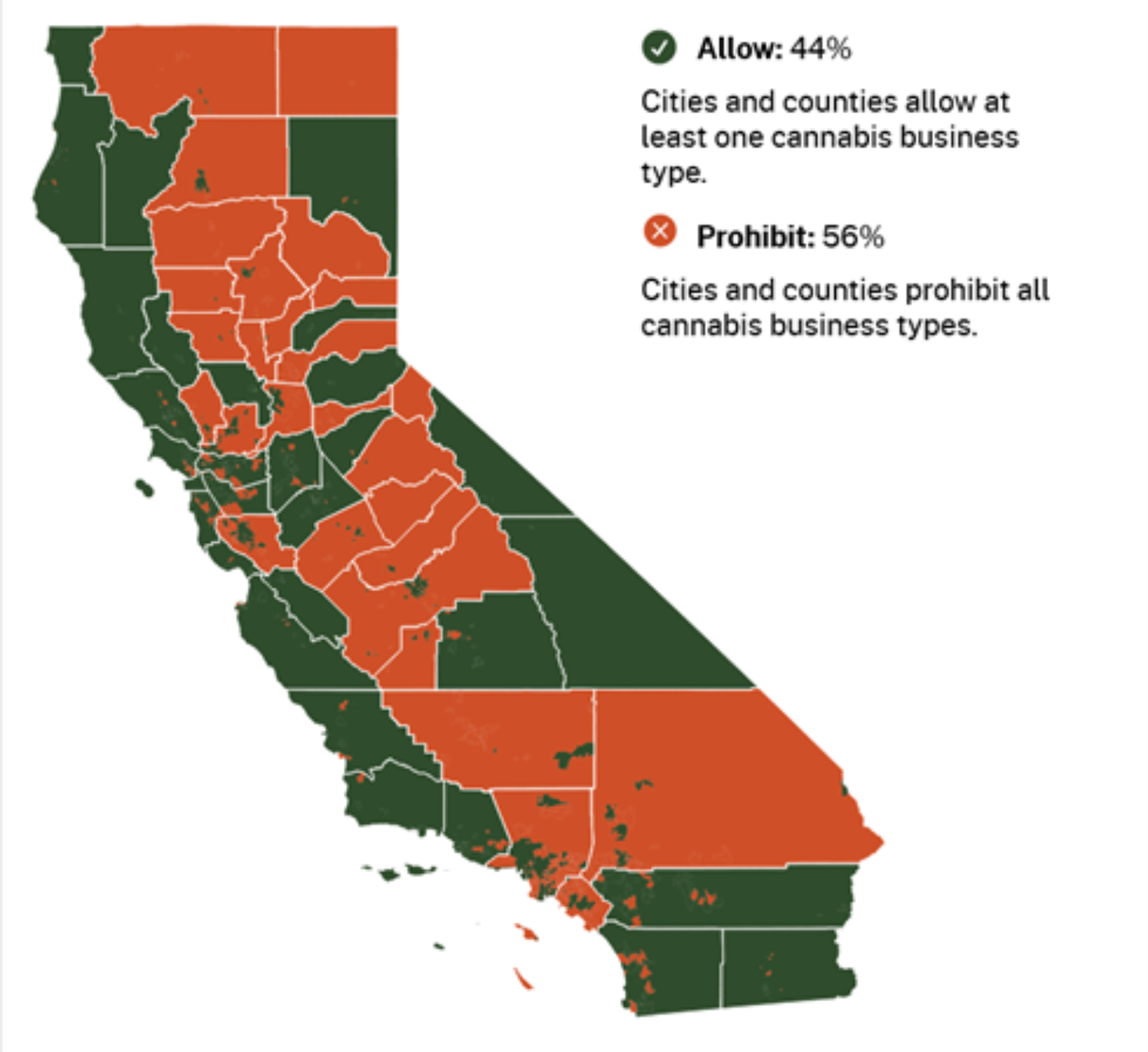

Among the many complex factors affecting who can obtain a cannabis license in California is that under Prop. 64 and subsequently MAUCRSA, each of California’s 540 cities and counties gets to decide whether to permit commercial cannabis businesses.[8] As a result, 304 out of 540 cities and counties continue to ban cannabis businesses entirely, and 370 jurisdictions prohibit cannabis cultivation.

Figure 3 Source: CA Dept. of Cannabis Control, Where Cannabis Businesses Are Allowed, 2022 (last visited Nov. 17, 2022).

While the state-sponsored media campaign This is California Cannabis promotes the licensed industry and aims to “encourage unlicensed cannabis operators to get licensed,” the application process itself can present additional barriers. One requirement is that applicants provide proof of their legal right to occupy and use a proposed site for commercial cannabis activities when applying for a license.[9] At the same time, applicants are barred from engaging in commercial cannabis activity until the issuance of that license,[10] which can be prohibitively expensive for some applicants paying rent or mortgages while waiting for applications to be processed. Some support is available through equity grants, although programs vary throughout the state. For the past four years, grant solicitations from the Governor’s Office of Business and Development have stated that the purpose of the Cannabis Equity Grants Program for Local Jurisdictions is “to advance economic justice for populations and communities harmed by cannabis prohibition and the War on Drugs….” Similarly, the needs-based application and license fee waiver qualifications specify arrests, convictions, or those “disproportionately harmed” by cannabis criminalization as eligibility factors.[11] Perhaps ironically, all three counties constituting the state’s famed “Emerald Triangle'' (Humboldt, Trinity, and Mendocino) consider experiencing or living near past CAMP eradications to be a qualifying equity factor for those impacted by the War on Drugs within their jurisdictions.

Medical cannabis cooperatives and collectives protected from criminal sanctions under California’s Medical Marijuana Program (MMP) were exposed to an increased risk of criminal liability following Prop. 64 and MAUCRSA. From 2004 until 2019, the MMP exempted medical cannabis patients and caregivers operating a not-for-profit cooperative or collective from arrest or prosecution.[12] [13] Implementing the state’s commercial cannabis license system triggered the start of a one-year, statutory countdown to automatically repeal legal protections for these patient groups. Id. at n.11. The clear expectation was that medical collectives and cooperatives had one year to obtain a state license before facing criminal liability. But not all patient groups were designed to operate as businesses under the commercial licensing structure, while others were located within the 56% of jurisdictions prohibiting cannabis businesses. Notably, local governments were not required to allow medical cannabis cultivation even under the MMP. However, the Fifth District Court of Appeal held in Kirby v. County of Fresno that while an ordinance banning medical cannabis cultivation did not conflict with the MMP, designating violations of the ordinance as a misdemeanor did violate the MMP’s prohibition on criminal sanctions against qualified patients and caregivers.[14] In 2019, one year since the first licenses were issued, the California Attorney General’s Office provided updated medical cannabis guidance alerting collectives and cooperatives that continuing to operate without a state license “may give rise to probable cause for arrest and seizure.”

Alternative Enforcement Strategies

MAUCRSA did create administrative methods for addressing unlicensed cannabis cultivation. Established as Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 26038, it imposes civil penalties for unlicensed cultivation, with fines ranging up to $30,000 per violation, which is defined as each day of operation. Knowingly acting as an employee or landlord of an unlicensed business carries penalties of up to $10,000 per day. The agency tasked with regulating commercial cannabis activity, the California Department of Cannabis Control (DCC),[15] has reported final decisions on three civil penalty cases. Among these, one cites Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 26038 authority to impose a single-day penalty of $9,000 for a business that hosted an unlicensed cannabis event amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. An additional $32,772.50 was imposed to recover the costs incurred by DCC to investigate and prosecute the $9,000 fine. Meanwhile in July, 2022, DCC announced the latest results of their ongoing partnership with federal, state, and local law enforcement. Over the past year, DCC attended 208 search warrants, helping to eradicate “over 1.38 million cannabis plants.” The agency highlighted efforts they supported in San Bernardino County during “Operation Hammer Strike” which eradicated over 57,000 plants, and “Operation Green Day” in Stanislaus County, which seized “nearly $55.7 million worth of illicit cannabis plants, products, and illegally obtained cash.”

Although it is not as widely publicized, counties do also incorporate code enforcement into their cannabis enforcement strategies. Between May and October 2021, Mendocino County Code Enforcement abated 8,968 cannabis plants and collected at least $102,640 in fines for violations of the Cannabis Cultivation Ordinance. Mendocino County Code Enforcement’s abated plant total is on par with CAMP’s plant eradication total for Los Angeles County the same year. But during that time, CAMP eradicated 131,319 plants in Mendocino County, the second highest plant total of any county statewide.

California Cannabis Enforcement In 2023

On October 11, 2022, the California Attorney General’s Office announced that CAMP eradicated 973,894 plants, 203,872 pounds of processed cannabis, and seized 184 weapons from 449 sites throughout the state this year. It also announced the transition of CAMP into the newly formed Eradication and Prevention of Illicit Cannabis (EPIC) Task Force. Unlike CAMP’s annual 13-week season, EPIC represents a year-round effort. Despite the creation of a licensed cannabis industry, reductions in criminal penalties, and the expansion of civil authority, California continues to rely primarily on federal, state, and local law enforcement efforts to eradicate the unlicensed cannabis industry.

[1] Cal. Bus. & Prof. § 26000 (West 2017).

[2] 21 U.S.C. §§ 812(b)(1), 812(c) (West 2018).

[3] 21 U.S.C. § 844 (West 2010).

[4] 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(A) (West 2018).

[5] U.S. v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Co-op, 532 U.S. 483 (2001) ; Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005).

[6] Cal. Health & Safety Code §§ 11358-60 (West 2011) ; Cal. Health & Safety Code §§ 11358-60 (West 2016).

[7] See also California District Attorneys Association, Environmental Crimes and Civil Violations Associated with Cannabis Cultivation, 2019 (last visited Nov. 15, 2022).

[8] Cal. Bus. & Prof. § 26200 (West 2021).

[9] Cal. Bus. & Prof. § 26051.5(a)(2) (West 2022).

[10] Cal. Bus. & Prof. § 26038 (West 2022).

[11] Cal. Bus. & Prof. §§ 26249(c)(3)(A)-(D) (West 2021).

[12] Cal. Health & Safety § 11362.775 (repealed by S.B. 94, operative Jan. 9, 2019).

[13] Cal. Health & Safety § 11362.765 (repealed by S.B. 94, effective June 27, 2017).

[14] Kirby v. County of Fresno, 242 Cal. App. 4th 940 (2015).

[15] Cal. Bus. & Prof. § 26010.5(d) (West 2021).