Blog

Bring Back Medieval Insanity?

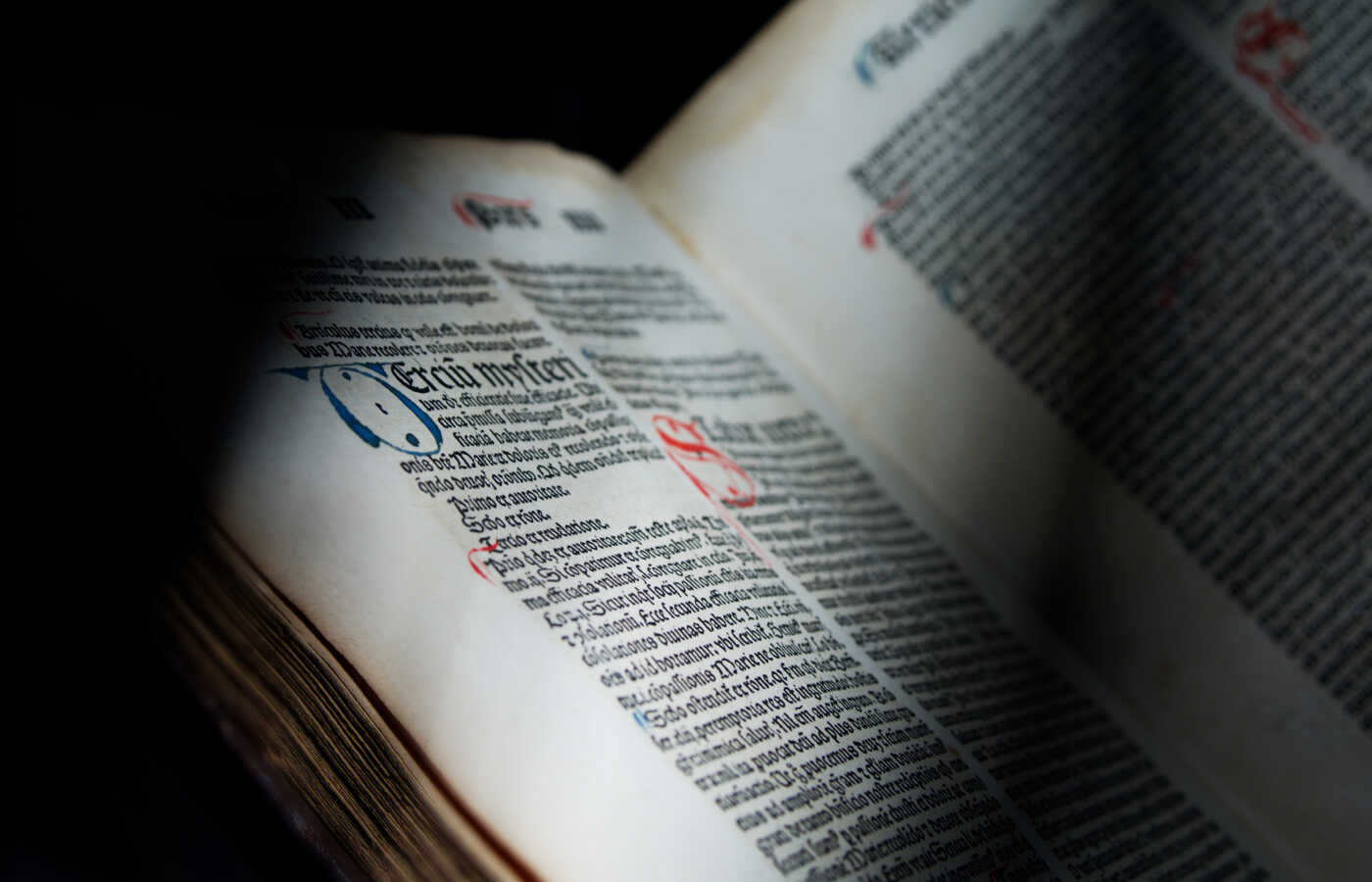

Photo by David Avery via iStock by Ghetty Images

No one praises medieval law. We look back on iron maidens, trial by ordeal, and death sentences for heresy or petty theft, and shiver in horror that such unjust societies existed. But how far have we come?[1]

The ancient insanity defense exempting certain severely mentally ill people from criminal punishment has narrowed sharply over time. No matter how mentally ill someone is, U.S. federal law lets individuals plead insanity only if they satisfy a two-prong test: “unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of [the] acts” at the time of the crime.[2] Some states also find defendants not guilty if they lack “substantial capacity” to follow the law.[3] Although the insanity defense is rarely asserted and rarely successful, policymakers restrict it in fear of the moral hazard of letting the guilty go free. Even when the crime is obviously the result of mental illness, juries often convict anyway.[4] Kansas has all but abolished the insanity defense, with Supreme Court approval.[5] Courts routinely exclude evidence of severe mental illness as a defense.[6] By contrast, medieval and early modern concepts of insanity look remarkably progressive.

Medieval law codes and legal theory conceptualized insanity very differently. Islamic law features a strong insanity defense, exempting “the insane until his reason returns” from criminal liability.[7] Medieval Islamic legal systems therefore did not prosecute severely mentally ill (majnūn) or disabled (mat’ūh) defendants.[8] However, insanity had no legal definition; anyone with severe mental illness would likely be considered insane based on a judge or local community’s subjective judgment, in which case they were placed under conservatorship.[9]

In theory, insanity was not always a complete defense. The law did not impose criminal penalties on insane people, but it held their guardians responsible for damages.[10] Prisoners who became insane after their crime could be released—but then reincarcerated if they recovered.[11] Some, but not all, judges refused to accept insanity as a defense for blasphemy, a capital crime.[12] In one case, a man named Fath al-Din, who seems to have been an aggressively profane but entirely sane secularist, was arrested for blasphemy and sentenced to death by a judge from the Maliki school.[13] His friends tried to transfer his case to the chief judge for the Shafi’i school, who opposed blasphemy executions, by trying to convince him that Fath al-Din was insane. The Shafi’i judge was apparently willing–in principle–to take the case and acquit Fath al-Din, but refused to do so because he was convinced of Fath al-Din’s sanity.[14] Apparently, some courts were willing to recognize an insanity defense against a charge of blasphemy if the facts fit.

Early Spanish law, on the other hand, had a theoretically restrictive insanity defense, but applied it widely. In the influential Siete Partidas (c. 1265), Alfonso X of Castile exempted “one who is so insane that he does not know what he is doing,” since such a person “did not commit the act with intelligence, and the same guilt cannot be imputed to him as to another in possession of his senses.”[15] This is the single-prong insanity standard, requiring unawareness of the nature of the act.

The Siete Partidas became the foundation of Spanish law, but in practice created something close to a general exemption from prosecution for the mentally ill. By the eighteenth century, “a demented person could not be punished for crimes that he committed,” nor executed after becoming legally insane.[16] Even the infamous Spanish Inquisition avoided prosecuting mentally ill defendants. Although doctrinaire inquisitors warned their colleagues that defendants were merely faking insanity, in practice the Inquisition rejected that view.[17] Diego de Simancas, a canon law professor and consultant for the Inquisition, argued that even temporary emotional disturbance through caused by rage or even love qualified for an insanity defense.[18]

Accordingly, the Inquisition stopped its investigation of Juan de Santarén, a priest denounced for heretical statements, after learning that he suffered from intermittent seizures and self-harm.[19] In 1549, the Cuenca inquisition decided that a hermit who had declared himself the Messiah did not meet the legal definition of insanity.[20] However, the Inquisition clearly realized the hermit had severe mental illness, and sent him to a mental hospital on the theory that his heresy couldn’t otherwise be addressed.[21] Like some Muslim scholars, some inquisitors believed that a few crimes could not be excused by insanity, such as blasphemy or lèse-majesté, but in practice tended to excuse mentally ill prisoners from punishment.

For the Inquisition, the insanity defense was especially comforting. The Inquisition believed that its orthodox interpretation was objectively and logically true. Therefore, obstinate heresy could only come from wickedness or insanity.[22] Insanity meant that the heretic was in fact a good person trapped by mental illness, and the inquisitor could sleep at night. A particularly humane inquisitor could have persuasively argued that the logical truth of orthodox doctrine is so obvious to a sane person that anyone promoting heresy is definitionally insane and should not be prosecuted.[23]

The Nahua people of what is now central Mexico took almost the opposite view: mental illness is a symptom, not a cause, of antisocial behavior.[24] The Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España, an early colonial description, lists the “madman” (iollotlaueliloc) under the category of “vicious” people. Aside from the classical Nahuatl style, it could be a rant against homeless people today:

The deranged man is perverse, sickly, poor. The deranged man goes about drinking crude [new] wine; he goes about besotted; he is possessed. He gives offense; he is oppressive; disrespectful; he meets no one’s gaze; he scatters hatred; he spreads hatred.[25]

By contrast, the Historia has more empathy for actual crimes. Its thief is “poor, miserable, useless, full of affliction, undone…He pants; his heart flutters. He slavers; his mouth waters.”[26]

So why was sixteenth-century Nahua society harsher toward mental illness than the Spanish inquisition?

The obvious answer is imperialism. The Nahua scholars behind the Historia lived through years of war, plague, and oppression by the colonial Spanish government, which evangelized with the message that, among other things, the Nahua deserved it. Nahua elites, in particular, had to aggressively and adroitly navigate the colonial system in order to maintain some level of personal freedom, respect, power, and property. In that context it makes sense for elites to contrast themselves harshly against people who lacked the psychological ability to cope with this system.

However, the Historia also uses the concept of madness to make value statements. The text describes dozens of types of people, first the “good” version, then the “bad” one. “The good old woman is a supervisor, a manager, a shelter.” The good nobleman is “a consoler, an animator of others” who “shows honor to others.” The bad young man is “crazed, dissolute, mad,” the bad nobleman “a fool, irresponsible, evil in his talk, crazy…mad, a vile brute.”[27] Consistently, the good person is supportive of others, while the bad one is “mad” because—and insofar as—they do antisocial things.

For the Historia, mental ability as such isn’t the problem (the good great-grandmother is “accorded glory” despite being “childish in her old age”). It condemns mental illness leading to perceived antisocial behavior because being a good person means doing prosocial things. For the Inquisition, on the other hand, mental illness was tremendously helpful. The insanity defense served the Inquisition, but not the Nahua philosophers.

Finally, medieval Jewish law also stigmatizes mental illness, but provides wide legal protections to mentally ill people. The 12th-century Spanish-Egyptian physician and legal scholar Moshe ben Maimon, known as Rambam, wrote that a mentally unstable person:[28]

is not obligated by the commandments. A mentally ill person is not just someone who goes around naked or breaks vessels or throws stones. Rather anyone whose mind [da’at] is torn [or] whose mind is always confused on a certain issue even though he can speak and ask questions relevantly on other issues…The unsettled or those whose minds are seized or who are severely deranged fall under [this] rule.[29]

Similarly, seriously mentally disabled people are legally incompetent if they “do not understand [when] statements contradict each other, [or] do not understand the details of an issue as most people can.”[30] Unlike in Nahua culture, cognitive rather than moral capacity is the issue.

Like Islamic law, Rambam refused to set a specific insanity test, instead leaving the decision to “what the judge sees, since it is impossible to describe the mental state in writing.”[31] However, he set a stark binary division not just between legal sanity and insanity but between legal capacity and incapacity. For Rambam, someone is either obligated to follow the law (ben hamitzvot) and a legally competent adult, or exempt from all legal consequences and totally incompetent, barred from public and religious life.[32] Rambam defines mental incapacity so broadly as to give most mentally ill people blanket immunity from prosecution; imagine a government that simply could not punish people with schizophrenia or substance use disorders. Why?

Rambam lived in an unstable world where the state routinely turned its power against unpopular minorities. He fled fragmented Spain when an anti-Jewish movement took power there, and only found safety on the other side of the Arab world, as a doctor at Salah al-Din’s court in Egypt. Rambam did not trust the sultanate. As the court doctor, he served the whims of every prince and officer. He worked himself to exhaustion hoping for the “salvation” of his “afflicted people.”[33] He wrote the Mishneh Torah to be useful, but also, perhaps, so he could have the luxury of imagining a just society. For Rambam, it is wrong to punish people for violating laws they cannot fully comprehend. Nothing else matters.

These concepts survive. Sharia courts still resolve disputes. The Siete Partidas left their legacy in law from Barcelona to Tierra del Fuego. Nahua culture remains vibrant. Hundreds of thousands of people follow the Mishneh Torah. The U.S. legal system has rapidly processed millions of people into prison by sharply curtailing the insanity defense. Medieval policymakers, on the other hand, used the insanity defense to protect severely mentally people from prosecution regardless of whether they satisfied a narrow test, relied on families to care for mentally disabled people, valued the ability to serve prosocial roles, and refused to prosecute people based on absolute standards of justice rather than perceived utilitarian efficiency. They were not perfect; medieval records mention no support to families to care for their relatives, and medieval mental hospitals did not even pretend to treat patients humanely, much less effectively. But their worldview reflects a concern with justice over efficiency that the legal system would do well to adopt.

[1] See Robert Bartlett, England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings, 1075-1225 183 (Oxford University Press, 2002). A majority of trial by ordeal participants were in fact found not guilty, compared to the U.S. system which effectively forces guilty pleas in a vast majority of cases.

[2] 18 U.S.C. §17(a).

[3] See Blake v. United States, 407 F.2d 908, 908 (1969) for an example of the standard once used by federal courts and retained by some state courts.

[4] See State v. Green, 643 S.W.2d 902, 902 (Tenn. 1982); Yates v. State, 171 S.W.3d 215, 215 (Tex. App. 2005).

[5] Kahler v. Kansas, 589 U.S. 271, 271 (2020).

[6] See People v. Brady, 22 Cal. App. 5th 1008, 1010 (2018).

[7] Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Musnad al-Imām Ahmad b. Hanbal, Hadīth no. 24738 6, 100.

[8] Muhammad Ahmad Munir & Brian Wright, Reshaping Insanity in Pakistani Law: The Case of Safia Bano, 49 Am. J. of L. & Med. 301 (2023).

[9] Id.; Michael Dols, Insanity in Medieval Islamic Law, 2 J. of Muslim Mental Health, 81 (2007).

[10] Dols, supra note 9, at 87.

[11] Id. at 90.

[12] Id. at 116.

[13] Id. at 103.

[14] Id. Fath al-Din’s friends also wanted the Shafi’i judge to take the case because the judge “did not agree with the execution of someone who pronounced the declaration of faith.” Apparently the judge, like many Muslims before and since, did not want to execute defendants for blasphemy, and his method of avoiding this was to reason that someone willing to say the declaration of faith could not be a blasphemer, and therefore dismiss blasphemy cases whenever the defendant was willing to recite the declaration of faith. It’s not clear why the judge didn’t adopt this strategy after concluding Fath al-Din was sane, but he likely had limited political ability to take cases from the Maliki court.

[15] Siete Partidas I § XXI.

[16] Ruth Pike, Capital Punishment in Eighteenth-Century Spain, 36 Histoire sociale–Soc. Hist., XVIII 375, 381-382.

[17] Sara T. Nalle, Insanity and the Insanity Defense in the Spanish Inquisition, Soc’y for Spanish and Portuguese Hist. Stud. 3-4 (1992).

[18] Id. at 5.

[19] Id. at 7.

[20] Id. at 8.

[21] Id. at 8-9.

[22] See Nalle, supra note 17, at 1. The Spanish Inquisition had, in theory, no jurisdiction over Jews, Muslims, or Indigenous people, unless they had already accepted Catholicism.

[23] I was unable to find examples of anyone actually making this argument; perhaps at some level the Inquisition knew that no ideology is so objectively persuasive.

[24] The Nahua people include the Mexica people often known as the Aztecs, and spoke and wrote in classical Nahuatl; contemporary Nahua people live in Central Mexico and the U.S.

[25] Bernardino de Sahagún and many Nahua students and experts, Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España. Colegio Imperial de la Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, 1577 10.11 (Nahuatl transl. Anderson and Dibble).

Sahagún was a contradictory and tragic man. A Spanish priest, he worked in Mexico as a cog in the machine destroying Native cultures. He justified his research on Mexican religion and culture by arguing the knowledge was needed to suppress non-Christian traditions, but also worked to demonstrate that Mexican philosophy and tradition deserved respect. Sahagún educated Indigenous nobility at the first European-style college in the Americas and taught them to practice Catholicism and write Latin hexameter poetry, but also to become powerful governors and administrators. He worked with his students, elders, and Nahua experts to compile an extensive record of central Mexican culture, the Historia, even as a plague cut down its people. Colonial authorities barred the Nahua postulants he’d trained from the priesthood and banned the Nahuatl Christian texts he’d championed. Sahagún sent the Historia to Spain as a lobbying effort; it was promptly censored. The Historia is written in facing columns of Spanish and classical Nahuatl, which roughly translate each other but have significant differences. It takes significant critical reading, because Sahagún and his collaborators interpret 16th-century Nahua culture through considerable filters and biases including their desire to emphasize compatibility between Nahua and Catholic Castilian cultures.

[26] Id.

[27] Id. at 10.3. The Historia repeatedly describes women as independent leaders; it harshly condemns alcoholism and drug use.

[28] Rambam is the Hebrew acronym for “our Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon,” but he is often cited as Moses Maimonides, Rambam, or Musa ibn Maimun al-Qurtubī.

[29] Moshe ben Maimon, Mishneh Torah. Cairo, 1180. 9 Edut [Testimony] §§ 9-10.

Mishneh translates to “restatement”; the Mishneh Torah condensed a millennium of Talmudic debates into a single code in simplified Hebrew. Perhaps alone among law codes, it was written to be easily readable by the public.

[30] Id. § 10.

[31] Id.

[32] Id. § 9.

[33] Moshe ben Maimon, letter to Shmuel ibn Tibbon, September 30, 1199. Rambam had a private medical practice and community work in addition to his court duties, so he worked about 90 hours a week into his sixties if we take him at his word (he wrote to discourage ibn Tibbon from visiting). Although he saw Salah al-Din every day, he never described their relationship except in terms of his obligations.